How To Push Canadian Politicians For Real Change Beyond Symbolic Gestures

The time for symbolic gestures over residential schools is over

Call it the pandemic paradox: at a time when everything feels legit unprecedented, the one thing that feels predictable is another head-on collision with truths we seemed better able to ignore before the pandemic, followed by public outrage calling for change.

Last summer it was Black Lives Matter marches in response to George Floyd’s murder in the US which grew into marches here in response to the suspicious death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, a Black-Indigenous woman in Toronto who fell 24 storeys to her death while police were in her home.

This summer it’s vigils and somber ceremonies for the children murdered in residential schools, sparked by the announcement in late May by the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc of 215 unmarked children’s graves found on the former site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

In between have been the ongoing shocks of skyrocketing anti-Asian racism in Vancouver and the Islamophobic terrorist attack in London.

None of these represents a one time occurrence: Black and Indigenous people have disproportionately suffered police violence since before Canada became a country. Asian and Muslim Canadians have been telling us for decades that systemic racism is exactly who we are as a country. But in these unprecedented times, truth has become harder to ignore.

So many urgent questions (again) about what we need to do to combat hatred in Canada.

There are no easy solutions but there are concrete steps we can take now, in honour of the Afzaal family and the little boy left behind. My latest.

https://t.co/mDGybhqOw3 via @torontostar— Amira Elghawaby (@AmiraElghawaby) June 9, 2021

The response of power-holders to these moments of reckoning with the brutal unresolved legacies of colonialism is anything but unprecedented. Whether it’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau or premiers and mayors across the country, we have come to expect tweets expressing shock and outrage. Then it’s the promise to do better followed by the token gesture: a bended knee, a half mast flag, a renamed street.

It’s hard to be critical of what seems like demonstrative concern — until the next confrontation rolls in, and it’s rinse and repeat while the impacts of racism continue unabated, and truths long known by racialized communities fade into the background for the majority of (white) Canadians.

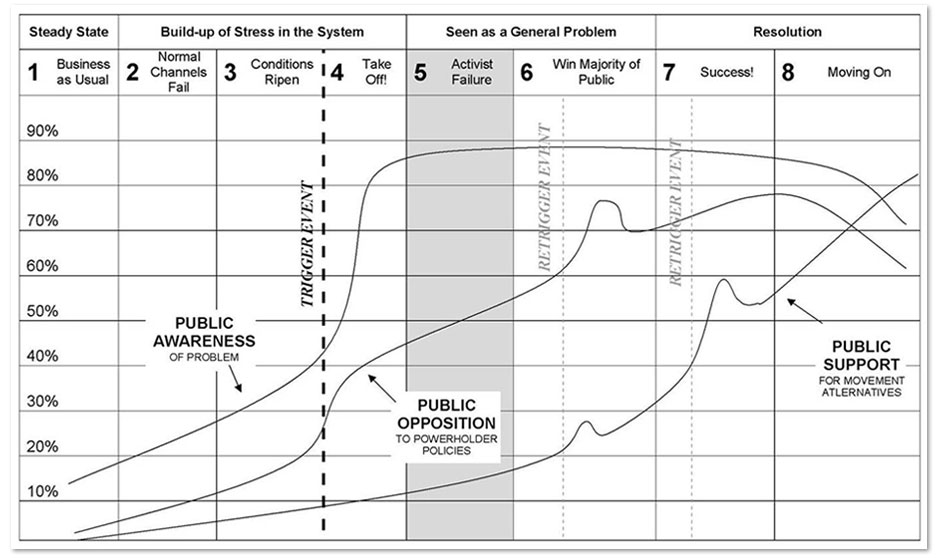

But anything that is so predictable is also possible to overcome. The Movement Action Plan (MAP) by Bill Moyer – an anti-nuclear activist from New England – was created to provide a framework to do just that. Here’s how it works.

The MAP asks us to consider a movement for change as a process with many stages. Just like you wouldn’t judge the success of a cake by the way it tasted when you’ve just mixed wet and dry ingredients, the success of a movement should be judged by how well it is doing at its given stage.

Unlike a cake, however, movements can take years to be fully baked and there are existing power-holders who do not want this cake baked at all.

How the power-holders work to prevent change is different over time. Moyer lays out eight stages that movements need to go through to be ultimately successful.

In the first stages of the MAP, the main goal is gaining legitimacy and getting the message out. A well-placed tweet from a power holder (such as an opposition elected official) can make a big difference for the movement to get to stage two.

Movement Action Plan

In stage two, symbolic gestures are still helpful to the movement. The goal at this stage is to show that the problem exists, and that incumbent power-holders perpetuate the problem. Movements typically achieve this by using legal tools – legislative committees, court cases etc. – to prove that existing institutions when functioning as designed are unable to solve the problem. Providing attention to these failures, or signing on as allies, supports the movement’s goal.

In stage three public awareness starts to rise outside of an initial core, and conditions for change ripen. Symbolic gestures are no longer sufficient.

While power-holders derive their power from the status quo, movements derive their power from the energy created by a public that has seen their values violated by existing policies and are motivated to fight to change that.

The job of power-holding allies at this point isn’t to show that they “get it” but rather to help the movement increase its energy.

A good contemporary example is one that I’m very familiar with and comes from my time on Vancouver City Council. In 2013 the City of Vancouver made a decision to invest significant resources into amplifying the Truth and Reconciliation’s (TRC) hearings when they were in the city by declaring a Year of Reconciliation, which culminated in a 70,000 person Walk for Reconciliation supported by the City but led by grassroots activists and leaders.

The attention the walk generated led to most other major cities in Canada also declaring years of reconciliation and starting to undertake their own work in partnership with local grassroots leaders.

Stage four is called “take off,” and it’s the critical stage for a movement to build power through energizing the public towards action. The public response to the findings of now more than 1,300 children’s graves at former residential school sites is a classic example of movement take off.

Join @SpiritBear & read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action in this free child friendly version. Residential School survivors asked all of us to make sure this work gets done. Top Calls to Action are about Indigenous children today. https://t.co/6xtMN2dhqx pic.twitter.com/vRnadORsb2

— Cindy Blackstock (@cblackst) June 26, 2021

When power-holders make symbolic gestures at this stage, they take energy away rather than add it by sending the message that they’ve got this, and people need not worry about it. The very fact that they think it’s a time for symbolic action shows that they don’t get it at all.

So what does this moment call for from truly enlightened power-holders? Moyer makes the distinction between official and operative policies. Official policies are the stated goals of a government while operative policies are what actually exists in law or practice. Canada’s approach to justice for Indigenous peoples provides an excellent example of this in action.

Contrary to the impression Trudeau may have given you this past week, Canada never held a TRC. It was an independent commission established in 2008 as a result of a court ordered settlement from a case survivors took against the federal government and churches. While governments like the former Vancouver council supported it, the active involvement of the federal government didn’t start until December 2015, when Trudeau committed to adopt the TRC’s Calls to Action.

However, the commitment has never been officially adopted and as a result, most of the operative policies remain unchanged. You may be surprised to know, for example, that there are more Indigenous children in government care right now than there ever were under the residential school system.

What “enlightened” power-holders should be doing at this stage is thinking about how they can add energy to the movement instead of diverting it. They should commit money and action to demonstrating new ways of doing things – ceding decision-making powers over street-naming to First Nations for example. They should provide the space and resources that the movement needs to organize to get to the next stage.

These are just a few examples and by no means do they guarantee success. There are still four more stages to go, but it’s at this stage that most movements stall out precisely because well-meaning (or not) elected officials suck out the energy. If you can’t add energy to the movement then, at the very least, it’s time to get out of its way.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate