How The COVID-19 Pandemic Revealed Canada’s Most Powerful People Have Less Power Than They Think

One of the starkest lessons of the COVID times has been the unmasking of power

I teach about power.

Whether I’m teaching grad students at UBC, climate activists or convening workshops with tech executives, I almost always open up with a simple exercise: I put people into small groups and give them 10 minutes to choose which of them is the most powerful.

Whether they know each other well, or have just met it’s always fascinating to watch. It inevitably comes down to three basic responses:

(1) The person with the highest rank admits it but demurs at seizing the power;

(2) The person with the highest rank gets designated but clumsily insists someone else is more powerful or;

(3) If ranks are relatively even, the group revolts and refuses to choose one person.

In the debrief, the elephant in the room takes a stroll to centre stage.

When I say ‘power’ most people think of, well, power — Presidents like Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Jair Bolsonaro. Prime Ministers like Boris Johnson and Narendra Modi.

No matter how high your rank is in grad school or the tech industry, these are generally not people you want to associate your brand with. No child grows up dreaming of one day ruling a country by bullying — or simply crushing — all opposing viewpoints.

Yet the one definition of power we are given as children puts people with those attributes — big titles and big countries — at the top of the heap and mysteriously out of our reach.

Clearly titles and population size haven’t given anyone special power over COVID. In fact, just the opposite. Much smaller countries and people with smaller titles have been doing a much better job of keeping case counts down and people alive.

As it turns out, power is not mysterious. It’s just masked, and intentionally so. It’s always been in the interest of people with titles to obscure the language of power. Without language, it’s impossible to have basic power literacy let alone build the power competency that may challenge their power. But in the COVID times, all the Kool-Aid in the world can’t hide that a title alone is useless against a virus.

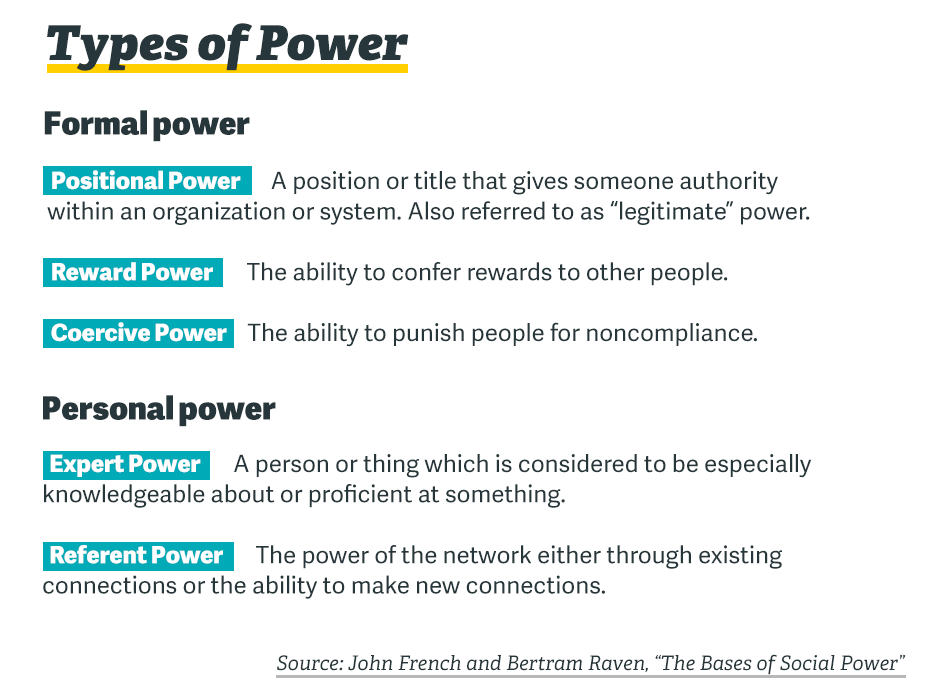

There are many different ways to classify power. One of the most durable comes from a study conducted by social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven in 1959 called The Bases of Social Power. They classify five bases of power: positional, reward, coercive, expert and referent power.

Types of Power, according to French and Raven’s “The Bases of Social Power”

While positional power is what we often use as a surrogate for all power, it is actually the most fragile — and COVID-19 daylights how fragile it really is.

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney is a Canadian example of a positional power approach. Relying on his authority as Premier as the main defense against COVID-19 in Alberta hasn’t been effective. Case counts are staggeringly high and, as a result, his government is polling terribly for Conservatives in Alberta.

Over in Ontario, Premier Doug Ford started out with the bluster of someone who thinks their title matters to a virus, but that quickly gave way to a curious mix of coercive and reward power. Essentially, the message has been do what we say, and you will get rewarded.

The challenge has been that expert medical advice was watered down by the Ontario government for political reasons and, as a result, despite the public following strict health orders, the real reward – lower case and death counts – never seems to materialize. Both coercive and reward power only work if you can deliver on the threat or promise. It’s increasingly hard for Ontarians to see either.

In British Columbia, Premier John Horgan has clearly ceded the leadership position on COVID-19 to expert power in the form of Dr. Bonnie Henry, the province’s chief medical officer of health. The challenge in a pandemic though is that with any given decision there is plenty to second guess. After all, no one can ultimately be an expert on a disease we’re still learning about. This challenge has in part blunted the effectiveness of Canada’s top doctor Dr. Theresa Tam, and highlights that Dr. Henry is as much helped by referent power as she is by her expertise.

Referent power, as outlined above, is the power of the network but it is also the power to build the network. It is the intangible quality of charisma. Most British Columbians have a sense that Dr. Henry feels our pain in a way those living in other provinces have not associated with their medical health officers.

As you can see, a leader can have more than one type of power. Effective leaders are able to access all five. However, it’s hard for leaders to tap into something they don’t have language for, and even harder for us as voters to demand.

But don’t we deserve someone who is not just a “prime minister” or a “premier,” but someone holding those titles who is also capable of exercising leadership through appropriate reward, expert, referent and even coercive power when necessary?

Context also matters. In the classroom exercise where I ask people to choose who is most powerful, there isn’t actually a right answer. The type of power that matters at any given time is determined by criteria relevant to the situation. In some situations positional power is enough, but in most situations positional power holders are a one-trick pony, and when that trick is ineffective, the positional power holder is too.

There will always be leaders who misuse power, we’ve had a few in the pandemic: All those ministers in Ontario and Alberta who went on tropical holidays over Christmas or the misspending at BC’s provincial health services authority.

It then becomes doubly important for all of us to understand that even though we may not have a powerful title, we all have power we can demonstrate and use in a democracy, whether it’s the reward of the vote or leveraging experts – academic, lived experience, or traditional knowledge-holders – in policy debates.

Even when a positional power holder makes it harder for those other powers to be used – there’s a reason people with authoritarian leanings defund science, ridicule the media and jail charismatic opposition leaders – it’s still not impossible to overcome.

Former Czech playwright and eventual President Vaclav Havel coined the term “Power of the Powerless,” which he defined as living one’s truth in the face of a society that tries to erase that truth. This is the power of the hundreds of thousands taking to the streets after the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the United States and Regis Korchinski-Paquet and Chantel Moore here in Canada. Before the pandemic, it was Greta Thunberg and the School Strike for Climate.

We always have a voice. Having language about power is something we haven’t had. Learning it and using it is the best tool we have to make change in our communities.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate