Why Powerful People Refuse to Take Action on Urgent Issues

Politicians often prefer to cause harm by not acting at all rather than causing harm by taking action.

Earlier in this six-part series on power and democracy I wrote a column about why powerful people do stupid things. For the last instalment, I thought I would write about an even more pervasive topic, which is why powerful people choose not to do anything at all.

As I write this column I am looking out my apartment window at a city built on top of a rainforest which is suffering from 42 straight days without rain. Five of those days were during a heat wave that the BC Coroner’s Service estimates killed 569 people and was five degrees hotter than any weather ever recorded here on the south coast.

The day the heat wave broke, the place that had recorded the highest temperatures – Lytton, BC at 49.6 degrees – burned to the ground in 15 minutes. There can be no question that the catastrophic impacts of climate change are here.

And yet just kilometres away from where I live, the Canadian government is building a new heavy oil pipeline with our tax dollars, seemingly unconcerned about the climate devastation this will contribute to.

“We considered we were immune to climate change, and that at most it would be a positive thing….But that’s not the way it works. It’s not just making it a little bit warmer. It’s creating these huge, extreme events. And that’s not just a Lytton problem.”https://t.co/8iAwSRQqDg

— Bethany Lindsay (@bethanylindsay) August 2, 2021

It’s not just heat. Although the sun is shining and there’s not a cloud in the sky, the mountains are hazy in the distance because the air quality is so bad. A little of that is wildfire smoke but much of it is a combination of human activity that – despite the fact that low air quality kills 15,300 Canadians per year – goes largely unchecked.

All of this is layered on top of other daily news stories. Millions of people cling to precarious jobs and unaffordable housing while governments rarely acknowledge that renters or precarious jobs even exist.

We continue to hear about the devastating unearthing of unmarked graveyards on former residential school properties that could have been brought to light sooner had the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action been heeded when the government accepted its report back in 2015.

Why no one knows how many children died inside Canada’s residential schools:

Locating victims have been hampered by destroyed and missing records – but also inaction by the federal government and Catholic Church.https://t.co/AuE7POkhWX #cdnpoli

— PressProgress (@pressprogress) June 6, 2021

Toxic drug deaths continue because elected officials won’t support safe supply. The housing crisis rages on because governments won’t regulate profiteering off of land and property.

If we know all this suffering, devastation and avoidable loss of human life is bad, why won’t governments act?

While advocacy organizations work hard to identify and remove barriers to action on these issues – lack of knowledge, lack of core constituency support, and campaign finance reform, to name a few – it turns out many people are hard-wired towards inaction through a mechanism dubbed “omission bias.”

In this context, omission means choosing harmful inaction over harmful action. Put another way, we would rather something bad happen because of what we omitted than have something bad happen because we inadvertently committed a harmful action.

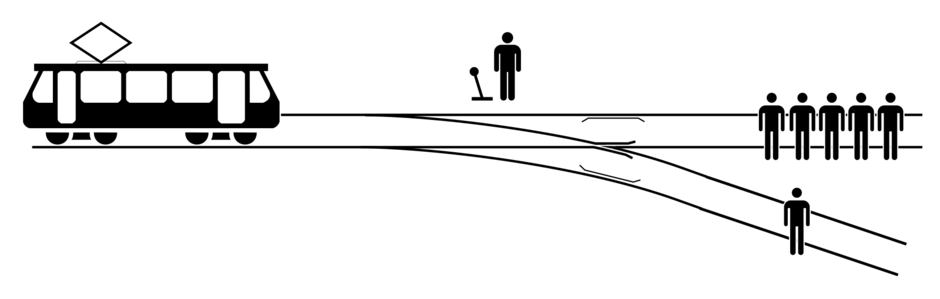

The most famous research done on this is the “trolley problem.” Research subjects were given a scenario where a trolley is speeding towards five people on a track. Various scenarios are proposed to save the five, each of which involves killing another person. The more actively involved people have to be in killing the one person, the less likely they are to choose saving the five people.

McGeddon, Wikimedia Commons

A similar trend even plays out in sports, where research shows that in professional basketball NBA referees call 50% fewer fouls during high stakes moments of the game, while in baseball umpires are 100% more likely to call a strike in error when the count is three balls than they are at lower ball counts to avoid accidentally sending a batter to first base.

If omission bias has this much impact on thought experiments and games where nobody’s actual life is at risk, you can imagine the outsized impact it would have in an environment where policy makers are the last line of defence for people’s health, safety and well-being.

The easiest path for omission-biased decision-makers can be simply to ignore the problem or put the causes of it in someone else’s hands. ‘People choose to be homeless,’ ‘people aren’t taking low-wage jobs because of CERB,’ ‘if China isn’t reducing emissions, why should we?’ etc.

Even when advocates have successfully proven there is a problem, the process in government of weighing all possible courses of action to find one that doesn’t inadvertently cause harm is glacially slow while many more lives are at risk from inaction.

There are consequences that arise from omission bias to those who chose to act as well. When I was first elected to city council, homelessness in Vancouver had risen by an average of 23% per year for each of the six preceding years. In my 10 years on council it slowed to an average of 3.8% per year. While any number above zero is too high, some of us felt it was at least a positive trajectory. Instead it was seen by critics as a failure of the government I was elected to.

By understanding the way omission bias works and accepting the impact it has on public policy if left unchecked, we can mitigate some of those impacts.

If omission bias means some power-holders are more inclined to take the path of least resistance, as advocates we should be fighting for policies that put human health and safety first, rather than simply providing an avenue to remedy bad outcomes.

Consider how this could work on climate policy. If environmental assessments required industry (or governments that own pipelines) to prove that LNG projects or heavy oil pipelines would cause zero damage to the climate before they could be approved, that would be quite different than the current model in which advocates have to try to prove through modelling and projections that new fossil fuel infrastructure will lead to the kind of devastation and loss of life that BC experienced last month.

LNG is regularly touted as a “transition fuel,” even as studies suggest it’s no cleaner than coal

If B.C. forges ahead with all planned #LNG projects, the province could exceed its 2050 climate targets by 227 per cent.

A fact check on LNG in B.C.:https://t.co/dRBimoyagO

— The Narwhal (@thenarwhalca) July 9, 2020

First up though is admitting we have a problem. Ask your MP, MLA, MPP, MNA or mayor what they are prepared to do to end the threats of climate change, precarious jobs and housing, homelessness, drug deaths and anti-Indigenous racism in your community. If the answer is “well, that isn’t really a problem our level of government can deal with,” then you have an omission bias denial on your hands.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate