Why The Full Impact of Hate Groups on Targeted Communities Is Not Captured By Hate Crime Statistics

Hate leaves hidden impacts on our communities

The recent terrorist designation of the Proud Boys and other white supremacist groups in Canada has generated headlines, along with justified criticism due to the deeply problematic nature of anti-terror legislation to begin with.

But what it hasn’t done is prompt a wider examination of the impacts of hate on marginalized communities.

While it is difficult to quantify, considering the dearth of research on the topic, there is enough evidence in Canada and internationally to demonstrate that hate has an insidious effect on social cohesion and on the well-being of targeted communities.

Even while hate crime statistics only tell a part of the story, given that two-thirds of victims have told Statistics Canada that they don’t report, there has been a troubling rise in police-reported hate crimes. This has coincided with the growth of far-right, white supremacist groups in Canada.

After all, as the American Psychological Association described in an informative study on the impact of hate commissioned by the Department of Justice Canada in 2008, hate crimes are also “message crimes in that the perpetrator is sending a message to the members of a certain group that they are despised, devalued, or unwelcome in a particular neighbourhood, community, school, or workplace.”

Members of the Proud Boys disrupt Mi’kmaw ceremony in Halifax in 2017 (CBC News)

Focused on a 2006 violent beating of a Sudanese refugee in Victoria Park in Kitchener, Ontario, the report makes it clear that a single hate crime can negatively reverberate throughout communities in ways that causes people to change their behaviours and perceptions of their own safety.

For instance, members of Kitchener’s African community were much more affected by the news of the beating than were others in the broader community.

In fact, many African community members reported “severe” symptoms of post-traumatic stress arising from the hate crime, compared to the general population which experienced only “mild” symptoms. Other risk factors, including being an immigrant and visible minority, having a lower annual household income, and having experienced discrimination, increased the likelihood of post-traumatic stress.

A significantly higher number of African community members also reported they were going out less, avoiding going out at night or alone, and avoiding certain areas of town.

This reinforces the point that hate crimes, or “bias-motivated violence” has a chilling effect on the entire community from which an individual or institution is targeted.

Soldiers of Odin marching Edmonton streets https://t.co/RZe1QotdHR #yeg

— CBC Edmonton (@CBCEdmonton) September 3, 2016

“[Hate crime] involves acts of violence and intimidation, usually directed toward already stigmatized and marginalized groups. As such, it is a mechanism of power, intended to reaffirm the precarious hierarchies that characterize a given social order,” chronicled Barbara Perry, Director of the Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism, at the Ontario Tech University. “It attempts to recreate simultaneously the threatened (real or imagined) hegemony of the perpetrator’s group and the ‘appropriate subordinate identity of the victim’s group.”

Exerting and demonstrating power is the calling card of white supremacist hate groups. In Canada, this has been demonstrated throughout social media platforms, online forums and chat groups, as well as in communities.

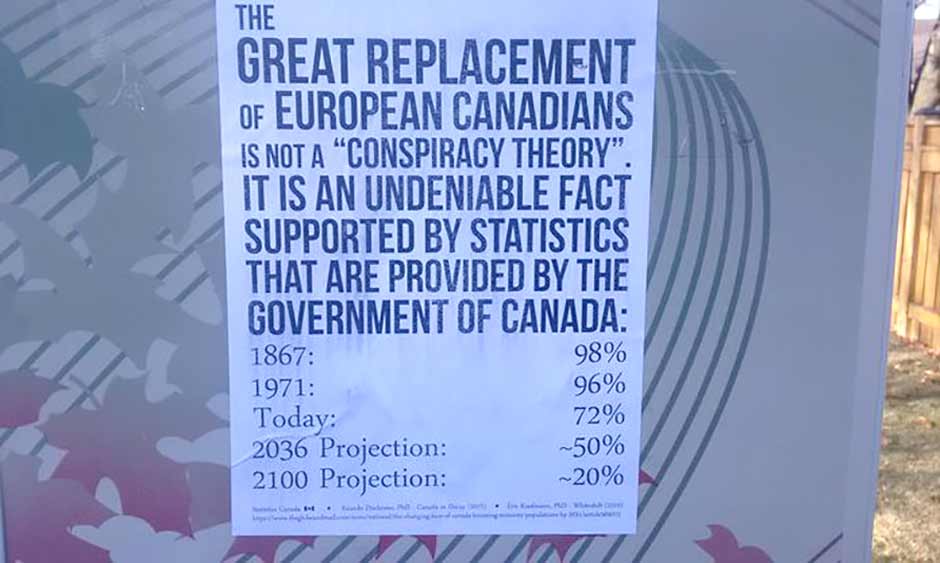

From incidents of racist posters emerging throughout Canada in recent years, including in Victoria, Peterborough, Toronto and Saskatoon, to acts of intimidation and outright attacks and murder by individuals linked with white supremacist groups or ideology, the reality is that far-right hate is a threat to far too many communities in our country.

Keith Richards (DurhamRegion.com)

Recent surveys by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation and the Mosaic Institute point to significant hate and racism on our social media platforms, experienced to a greater extent by racialized people.

Consider too the significant rise of anti-Asian sentiment throughout the pandemic as people unfairly stigmatized Asian Canadians for COVID-19. Reports of online hate grew, as did evidence of an increase in real life harassment, abuse, and physical violence, according to a survey by Angus Reid last June .

The Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice is working with researchers on a social media program to address the online targeting of their communities, demonstrating the urgency with which many communities treat the phenomena.

In recent months, a number of visibly Muslim women in Edmonton have been targeted in daytime attacks that have sent fear throughout these communities. “[It] shows an extremely alarming trend threatening the safety of the Muslim community,” Sgt. Gary Willits, an officer with the Hate Crimes and Violent Extremism Unit, said in a statement.

Women who wear the head covering can’t help but ask themselves why they continue to be the target of such blatant violence. Such questions are indicative of the internalized fear and questioning that comes with attacks on people’s personal identities. Even “in a global pandemic, we’re having a cold snap, everyone’s covered up but why are Muslim women still attacked? So I thought: Why is my hijab still a threat?” wondered Wati Rahmat, an Edmonton-based activist and blogger.

Whether in large or small towns, racism takes a heavy toll, even causing people to want to leave their homes, as shared by former refugee Felix Ndayitwayeko, in a recent CBC news feature. Ndayitwayeko wants to get out of Doone Street, located in Fredericton, New Brunswick, because racist acts against the large number of immigrant residents have become all too common.

Racist incidents in an area of public housing known as Doone Street in Fredericton have left some immigrants fearful of their own neighbours.

Read more: https://t.co/ORhv3h1FV7 pic.twitter.com/UVGXelLBaG

— CBC New Brunswick (@CBCNB) February 8, 2021

Hate changes how people exist within their own communities. It decreases their sense of well-being and attempts to diminish their identities. Society has a critical role in addressing these impacts.

A 2009 Ontario Human Rights Commission report, ‘Fishing without fear: Follow-up report on the Inquiry into assaults on Asian Canadian anglers,’ highlights a number of possible solutions, including ensuring that schools, law enforcement, various levels of government, relevant community groups and associations are working together to address hate in our midst.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate