One of the main options for electoral reform doesn’t meet the Liberals’ own “gender equity” test

So much for that idea.

Well, so much for that idea!

It turns out the best evidence we have shows preferential ballots – one option the Liberals are considering to replace our current voting system – may have trouble meeting their own stated criteria for reform.

During a press conference Wednesday, Democratic Institutions Minister Maryam Monsef listed “inclusiveness” and “gender equity” as two key outcomes of any electoral reforms.

That builds on what Monsef outlined as the main principles driving the Liberal government’s forthcoming changes to the electoral system last month, namely that any reforms need to increase diversity in the House of Commons.

That also echoes what Trudeau told an NGO that advocates for gender-inclusive workplaces earlier this month in New York when he was honoured for naming a gender-equal Cabinet.

Trudeau told the group Canada needs “to do more to address issues that negatively impact women,” adding that includes “achieving parity, not just in Cabinet, but Parliament as a whole.”

Hate to burst their bubbles, but if we’re going to talk about “inclusiveness” and “gender equity,” the evidence shows preferential ballot, in the way some Liberals are suggesting it be used, might not be the best way to get more women elected.

Here’s part of the confusion: preferential – or “ranked balloting” – isn’t an alternative electoral system on its own so much as a way of counting votes. It can be used in either a proportional system like many of those in Europe or in a majoritarian system like Canada’s first-past-the-post system.

If pursued by the Liberal government as currently expressed, preferential voting wouldn’t constitute a form of proportional representation and would merely change the way votes are counted under first-past-the-post – maintaining Canada’s unfair winner-take-all system.

Many of the worst features of first-past-the-post – such as false majorities, wasted votes, and strategic voting – would remain unchanged.

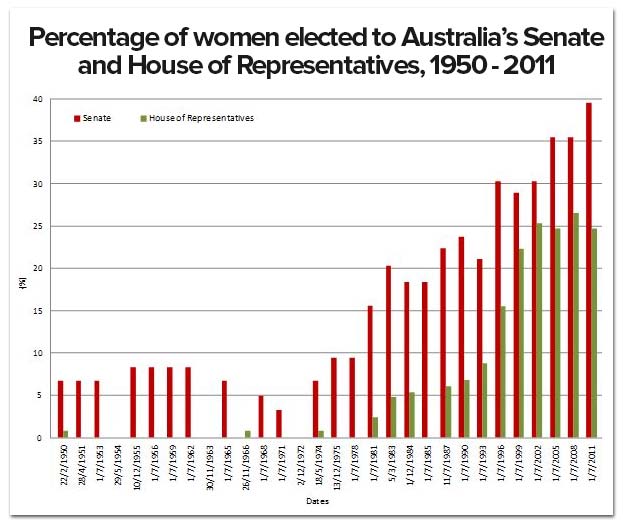

A good case study to look at on this question is Australia. Australia is unique in that voters elect its two houses using preferential ballot. But while its House of Representatives is majoritarian (first-past-the-post), its Senate is elected using proportional representation.

So with the same group of voters casting preferential ballots on the same day using two different systems, it turns out overwhelmingly more women are consistently elected to Australia’s Senate under proportional representation compared to representatives under a first-past-the-post type system:

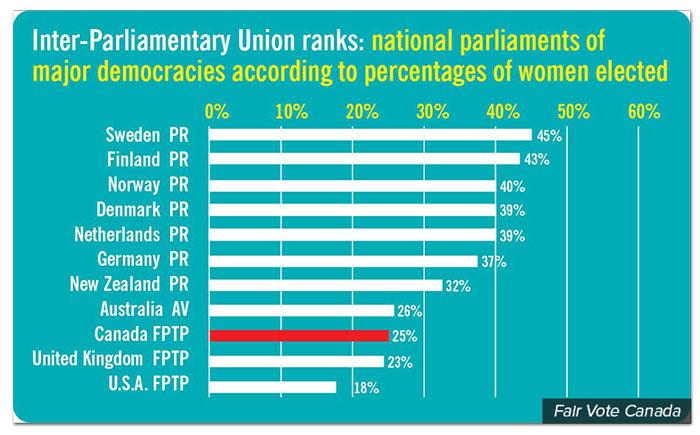

A similar pattern plays out around the world.

Several countries that use proportional representation consistently elect more women to their national parliaments than Australia’s preferential ballot/majoritarian system – or Canada’s current system, for that matter:

But, hey – that only matters if you think “gender equity” and increasing “diversity in the House of Commons” are important outcomes of any electoral reforms, right?

Photo: Canada2020. Used under Creative Commons license.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate