Winnipeg Police Agreed to Promote ‘Secretive and Strict’ Religious Sect, Internal Emails Show

Experts say internal emails suggest a controversial religious sect sought to use Winnipeg Police to generate positive publicity

The Winnipeg Police Service partnered with a “benevolent” community group on a charity food box program last year despite questions raised by local media outlets about the group’s parent organization — a secretive religious sect.

Internal emails newly obtained by PressProgress through Freedom of Information show Winnipeg police not only agreed to give the group positive publicity, but police were repeatedly pressed by the group into using their social media channels to give them “maximum exposure.”

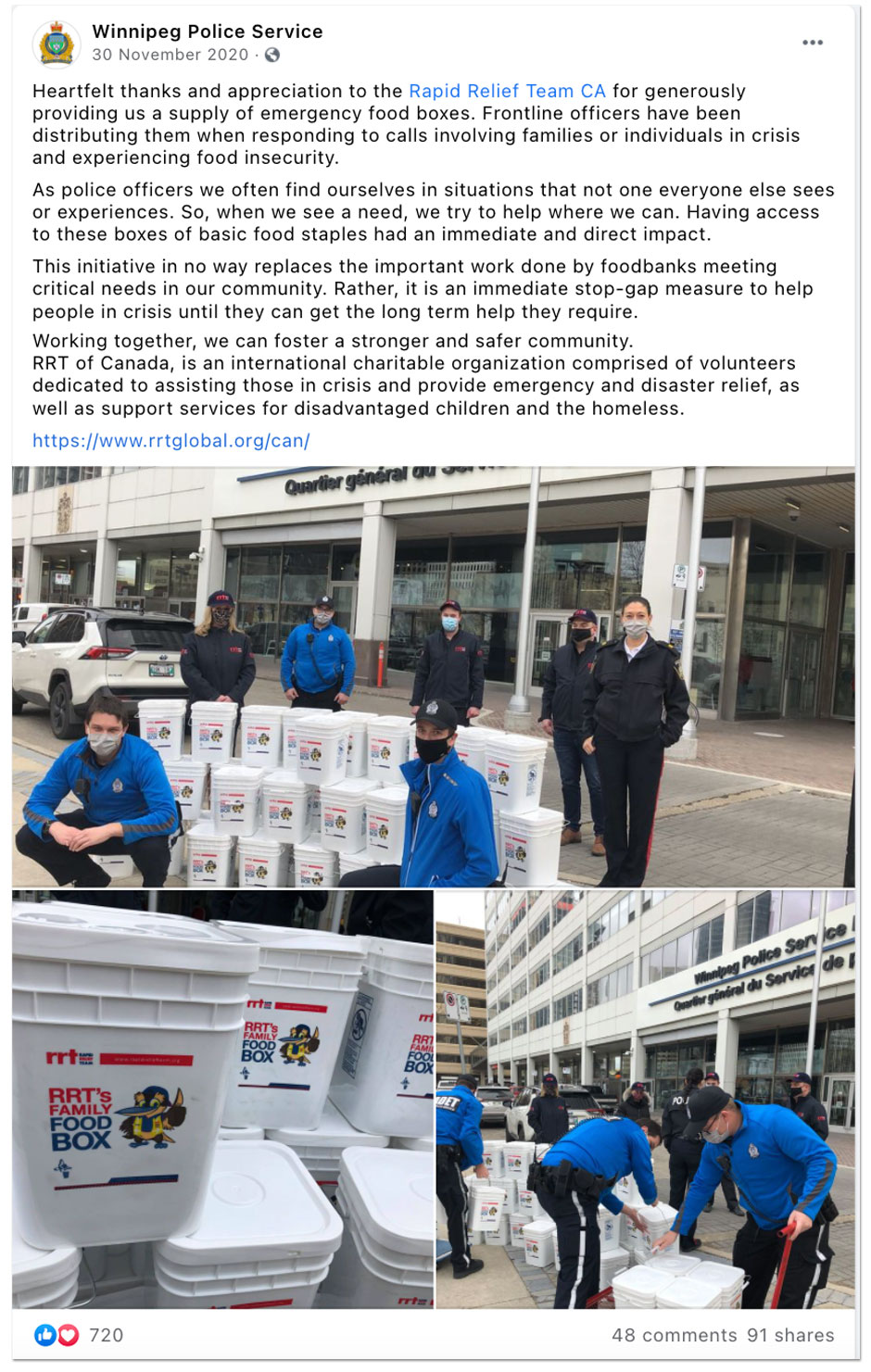

Between November and December 2020, a group called “Rapid Relief Team Canada” collaborated with the WPS to provide 130 emergency food boxes to people in crisis in Winnipeg. RRT characterized its food box program as an “emergency food bank.”

Police find people ‘at their most dire’ as COVID-19 magnifies struggles of poverty https://t.co/AhhH4pBOPR

— CBC Manitoba (@CBCManitoba) December 23, 2020

The program was publicized through the WPS Facebook and Instagram accounts and through local media like the Winnipeg Free Press and CBC Manitoba, though none noted the group’s ties to its parent organization.

On its website, RRT identifies itself as an “initiative of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church,” an organization previously described by the Winnipeg Free Press as a “secretive and strict” religious sect.

According to a 2014 Free Press investigation, former members described the PBCC as a “cult,” alleging that the PBCC limits members from interacting with “worldly people,” including not visiting the homes of non-members.

Although the PBCC disputed the Free Press’ reporting, the PBCC admits it practices a “doctrine of separation” and makes a “commitment to eat and drink only with those with whom we would celebrate the Lord’s Supper.”

On the FAQ section of its website, the PBCC goes out of its way to deny it is a “cult”:

“No, the Plymouth Brethren are not a cult. Established for over 180 years, the Brethren are a mainstream Christian Church that has more than 300 autonomous assemblies in 18 countries around the world and whose members extensively engage with the wider community on a daily basis.”

Plymouth Brethren Christian Church FAQ page

According to the BBC, “members follow a rigid code of conduct based very strictly on Bible teaching” and “keep themselves separate from other people (including other Christians) as far as possible, because they believe the world is a place of wickedness.”

The PBCC’s footprint extends across Canada and the world.

An award-winning 2017 memoir by UK academic and broadcaster Rebecca Stott documented her family’s struggle leaving the PBCC, formerly known as the Exclusive Brethren. In New Zealand, ex-members have alleged the PBCC uses abuse and intimidation, isolating individuals and breaking up families to maintain control.

Bill Redekop, author of the Free Press investigation, later called it “the biggest story for me in 2014” and described talking to ex- PBCC members as “chilling.”

ICYMI — A look inside the secretive and strict Plymouth Brethren sect in Manitoba by @BillRedekop: http://t.co/10WNMFEXka #longreads

— Winnipeg Free Press (@WinnipegNews) May 11, 2014

The PBCC also has a strong business focus, with approximately 450 members owning at least 25 small businesses and half of Stonewall’s industrial park in Winnipeg.

The PBCC directed all questions about the organization to the RRT. The RRT did not respond to multiple requests for comment from PressProgress.

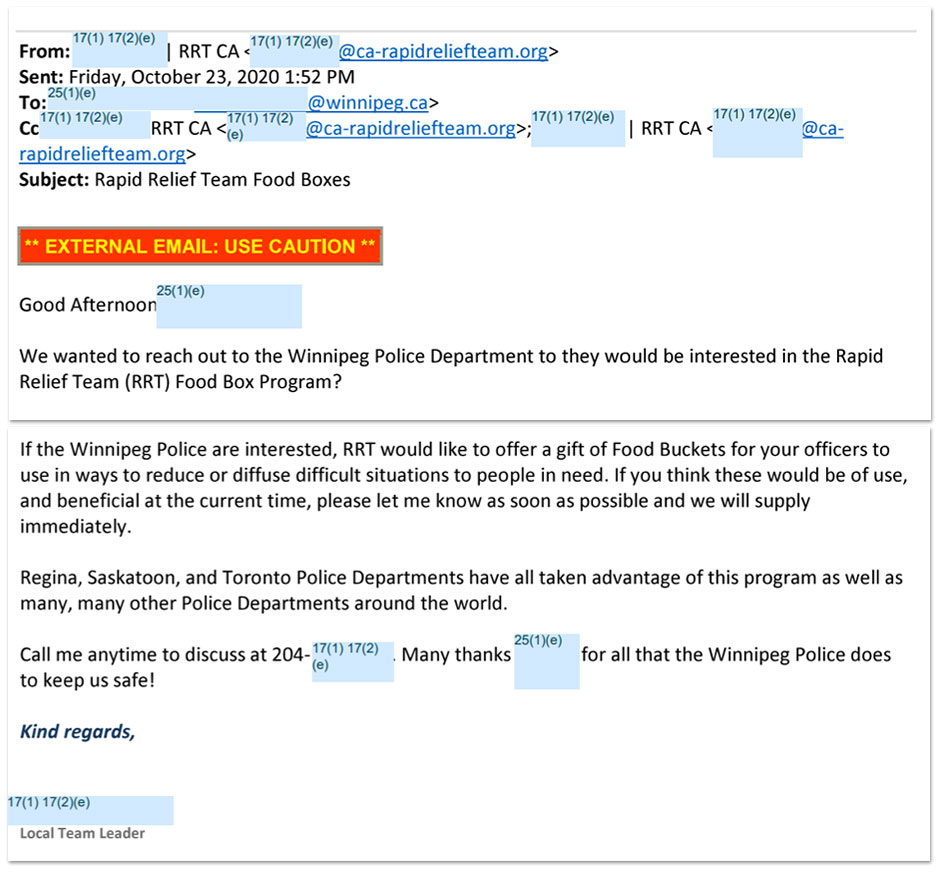

According to internal emails obtained by PressProgress from the Winnipeg Police Service, an RRT Local Team Leader first contacted the WPS on October 23 inviting the police to participate in the RRT Food Box program.

“Regina, Saskatoon, and Toronto Police Departments have all taken advantage of this program as well as many, many other police departments around the world,” the email noted.

The group’s promotional materials indicate that RRT’s food box program is “led by volunteers from the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church.”

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

Publicity was repeatedly discussed in several email exchanges with the Winnipeg Police Service’s community support division.

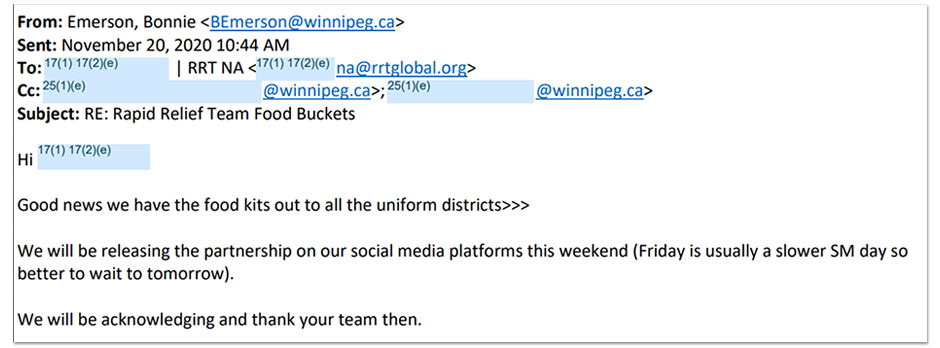

On November 20, Winnipeg Police spokesperson Bonnie Emerson had “good news,” updating the group that their food boxes had been distributed to police districts throughout the city.

“We will be releasing the partnership on our social media platforms this weekend,” Emerson wrote, explaining “Friday is usually a slower SM day so better to wait to tomorrow.”

“We will be acknowledging and thank your team then.”

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

Emails show that for the next few weeks, an “RRT Team Leader” pressed the WPS multiple times to share “stories of how Food Boxes have made a difference in this region,” along with photos and videos on social media.

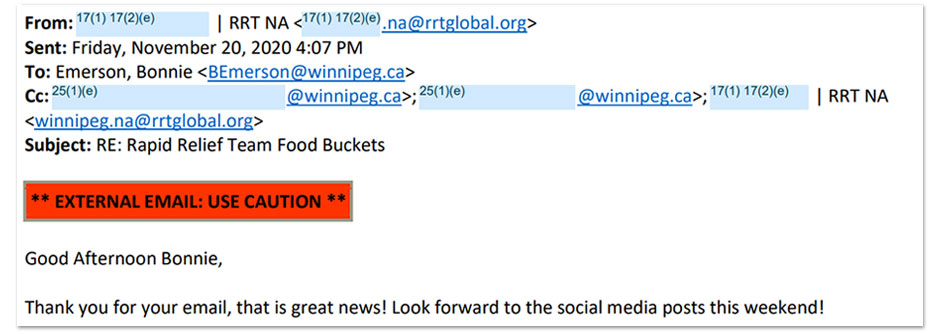

“Look forward to the social media posts this weekend!” the group replied to the WPS’ November 20 email.

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

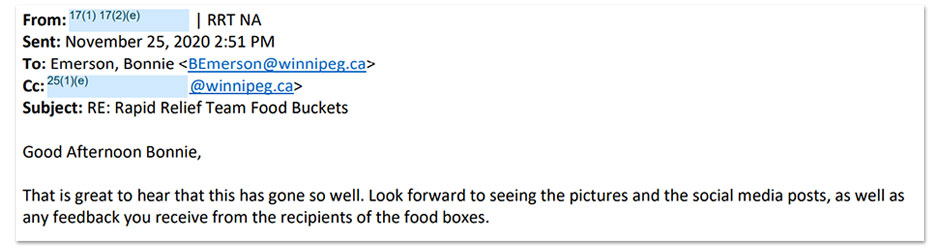

On November 25, the group wrote: “Look forward to seeing the pictures and the social media posts, as well as any feedback you receive from recipients of the food boxes.”

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

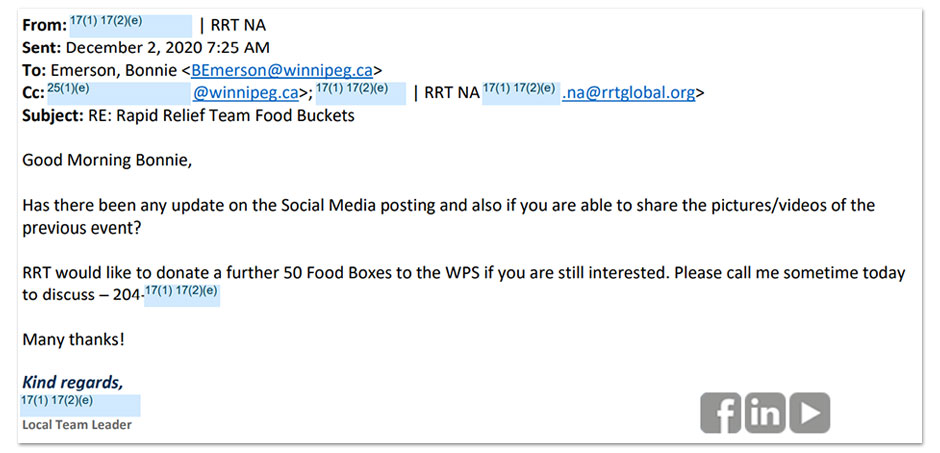

Again on December 2, the RRT Team leader asked: “Has there been any update on the Social media posting and also if you are able to share the pictures/videos of the previous event?”

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

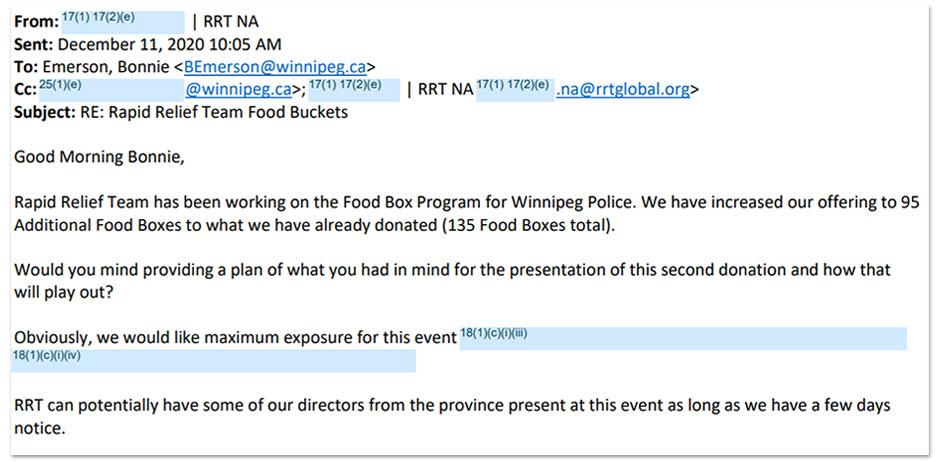

After the WPS shared photos of the donation on Facebook and Instagram, RRT donated an additional 90 boxes and requested “maximum exposure” for the event.

“RRT can potentially have some of our directors from the province present at this event as long as we have a few days notice,” the group noted.

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

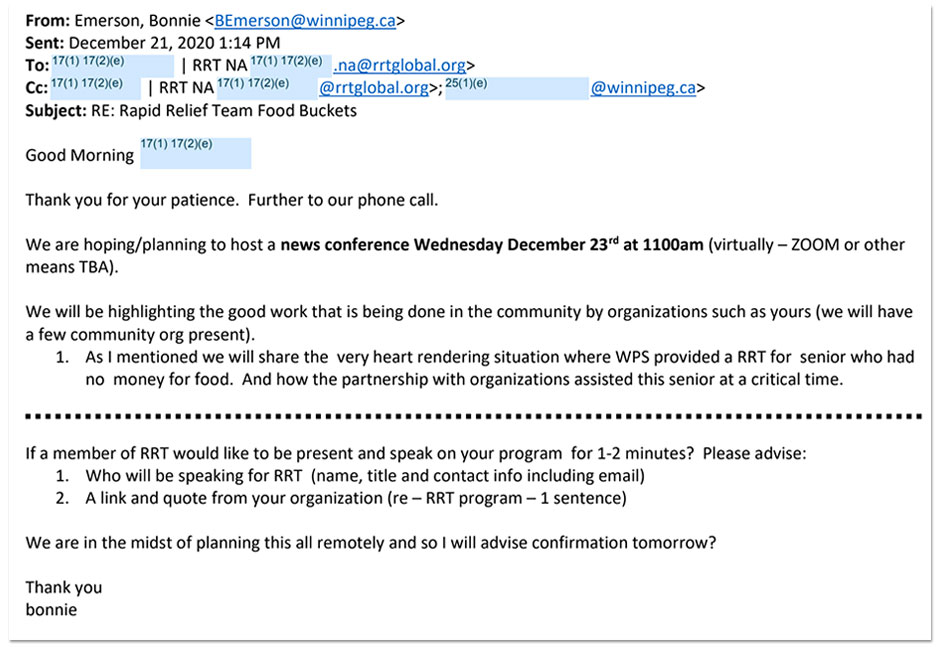

Winnipeg Police organized a Zoom press conference on December 23 to highlight the RRT donation and invited several other community based groups who also worked in food security to participate. However, the publicity photos only featured the RRT and the Food Boxes.

In emails planning the press conference, Emerson assured the RRT the WPS would “share the very heart rendering situation where the WPS provided a RRT for senior who had no money for food. And how the partnership with organizations assisted this senior at a critical time.”

Correspondence between Winnipeg Police and RRT Canada

Emerson included the story in a WPS press release and shared it at the press conference, which was republished alongside publicity photos handed out by police by CBC Manitoba and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Although RRT noted its affiliation with the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church in a backgrounder supplied to the WPS in advance of the press conference, that information was omitted from the WPS’ press release and social media postings.

Winnipeg Police Service (Facebook)

In a statement, Emerson defended the WPS’ partnership with the group, noting the police service works with over 100 different local health, community, justice and social services agencies to fulfill its mandate “to prevent crime in the long-term.”

“RRT approached the WPS to offer the kits and we accepted the donation as we were aware of community need,” Emerson told PressProgress.

“Police are often the first point of contact for people in crisis, and as a result we must be nimble to act on opportunities to connect persons in need, with organizations who can provide crucial assistance outside of our scope.”

Winnipeg Police did not address questions about their vetting process for partnering with community groups or whether they were aware of allegations of abuse from former PBCC members.

As far as concerns the WPS is allowing itself to be used to grant legitimacy to questionable groups, Emerson said it was simply letting the public know where to find help.

“Highlighting good work of community and arranging for social media or media involvement was (and) is important to ensure that citizens in need knew where or how they could receive help.”

Winnipeg Police Service

Stephen A. Kent, a sociology professor at the University of Alberta who studies new and alternative religions, said the email exchanges clearly demonstrate that the initiative was a “publicity-rich charitable activity.”

“The program fulfills the Rapid Relief Team’s charitable mandate,” Kent told PressProgress, noting “it provides photo opportunities that enhance the group’s image both to its own members and to an often-critical public.”

“The charitable donations are commendable, but former members still suffer from the group’s uncharitable policy of having been ‘withdrawn from’ their families and former friends who remain members,” Kent said.

University of Winnipeg criminology expert Bronwyn Dobchuk-Land said the emails suggest RRT was “anxious” about publicity.

“What’s really notable in the communications is how anxious they are about their public exposure,” Dobchuk-Land told PressProgress.“They revealed themselves to be primarily concerned with publicity in the context of their partnership with the police, and the distribution of these boxes.”

Dobchuk-Land said the partnership raises questions about whether the WPS knew of the PBCC’s history, given the allegations of former members, or whether the WPS had failed to do due diligence researching the group.

Dobchuk-Land said the WPS appeared “blatantly opportunistic” in the email exchanges for uncritically partnering with the RRT.

“If the police service failed to do their due diligence and partnering with an organization like this, what is relevant there is the question of who — when a group reaches out to the police — who do the police give the benefit of the doubt to in terms of imagining a legitimate partner?”

Dobchuk-Land points to a November 25 email, in which Emerson tells the group, “we have distributed the RRTF Food buckets to the uniform stations and in downtown and in the north end they are almost gone. I had not anticipated that this happen so quickly. The response has been overwhelmingly positive and it has exposed a need for sure,” later adding “it looks like the need is higher than even I anticipated.”

“How on earth could you be surprised at the need for free food in Winnipeg?” Dobchuk-Land said.

“I don’t know whether that was just something she fired off in the email or whether she was genuinely so disconnected from community needs that she wasn’t aware of the massive food insecurity that exists. It struck me as really ignorant.”

According to Manitoba Harvest, the food bank prepares hampers that feed 80,000 Manitobans every month.

Winnipeg homeless shelter Siloam Mission says it serves an average of 460 meals a day, three times a day.

“This initiative in no way replaces the important work done by food banks meeting critical needs in our community. Rather, it is an immediate stop-gap measure to help people in crisis until they can get the long term help they require,” the WPS stated in their November 30, 2020 Facebook post.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate