What happens next in British Columbia?

It's BC's first minority legislature since 1952.

More than two weeks after a closely-fought election night, the results are (finally) in.

And it turns out that, recounts and absentee ballots notwithstanding, none of BC’s three major parties has a majority of seats in the legislature after all.

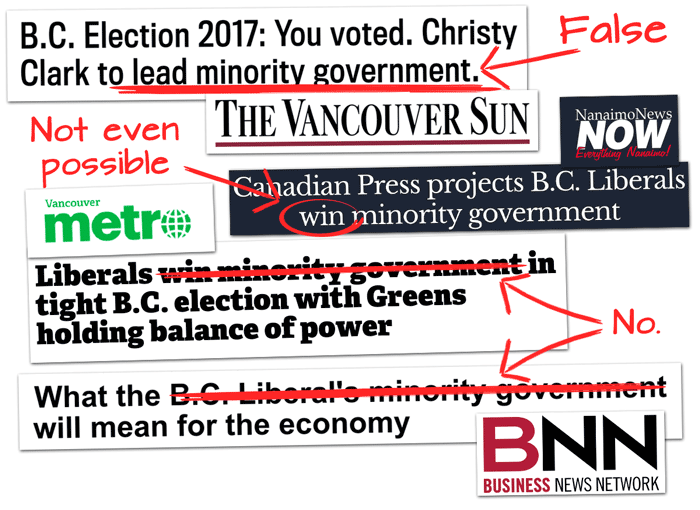

So, what exactly happens now? If you’re unsure, you’re not alone. In fact, quite a few headline writers don’t seem so sure either.

Since the election some parts of the media have painted an incorrect picture of what happens in the event no party wins a majority of seats — offering up bogus headlines suggesting the Liberals have either “won” (or “maintained”) a minority government.

Far from it, in fact.

While the final vote tallies have given the Liberals a plurality of seats they have yet to form a government, which requires support from a majority of MLAs in the BC legislature.

So, with 43 Liberals, 41 New Democrats, and 3 Greens officially elected to BC’s 87-seat legislature, what happens now?

What’s next?

Put simply, what happens next will be determined by a (potentially messy) combination of constitutional procedures, conventions, and political negotiations.

In order for any party leader to form a government, they must first win the confidence of the legislature.

And this is where things start to get interesting.

Here’s how the Mowat Centre’s Mark D. Jarvis explains the conventions of government formation in Canada:

Again people, the rules of government formation.Have them tattooed on you. pic.twitter.com/JAV4td4JfC

— mark d. jarvis (@markdjarvis) September 5, 2015

As the incumbent premier, Christy Clark in theory gets the first kick at the can.

But if Clark finds herself unable to command the confidence of a majority of MLAs, NDP leader John Horgan may have his own opportunity to form a government.

A great deal hinges on what Lieutenant-Governor Judith Guichon decides to do in the event Clark is unable to win the confidence of the legislature — by failing to pass a Throne Speech or in the face of an agreement between the NDP and Greens.

If either happens, Clark could request another election.

But Guichon might deny that request and give the NDP a chance at forming a government of its own.

Coalitions and accords

Both coalition governments and governing accords are the norm in many countries around the world.

And, though somewhat rare in Canada, they’re not entirely unheard of — having appeared in one form or another in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, and quite recently in Ontario.

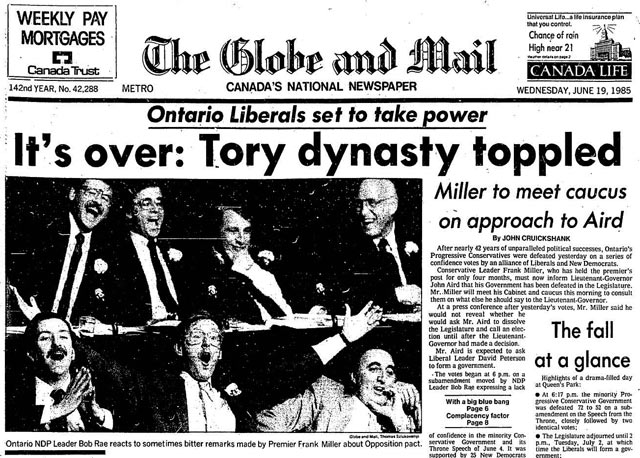

After the 1985 Ontario provincial election, Progressive Conservative Premier Frank Miller was forced out shortly after losing his majority.

Though the PCs technically had more seats some argued they had lost the confidence of the electorate and, for democracy’s sake, should yield the floor to the next largest party (in this case, the Liberals).

Liberal leader David Peterson and NDP leader Bob Rae then signed an accord and the PCs were forced to relinquish power.

Is BC in 2017 about to be a redux of Ontario in 1985?

Photo: Mohit_K. Used under a Creative Commons License.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate