One reason why the Tim Hortons-Burger King deal looks sketchy

It’s official: Tim Hortons and Burger King have struck a deal to create the world’s third-largest quick service restaurant company. People on both sides of the border have been quick to call Burger King’s planned acquisition an example of a tax inversion — a way for American corporations to dodge their tax duties by merging or acquiring […]

It’s official: Tim Hortons and Burger King have struck a deal to create the world’s third-largest quick service restaurant company.

People on both sides of the border have been quick to call Burger King’s planned acquisition an example of a tax inversion — a way for American corporations to dodge their tax duties by merging or acquiring a company in a foreign country with lower tax rates. (In this case, Burger King will retain its Miami headquarters, while the conglomerate’s address will be in Oakville, Ont, Tim Horton’s stomping ground.)

But it could be a little more complicated than that.

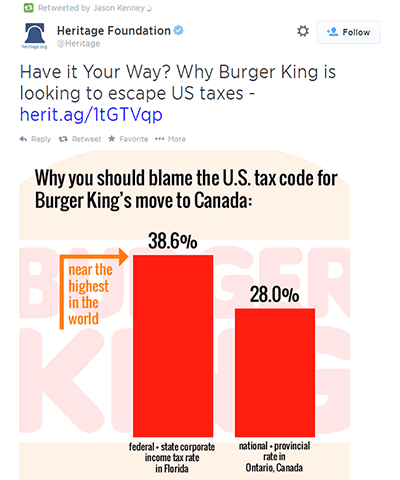

This does not appear to have anything to do with the corporate tax rate

The problem with calling this a straight-up tax inversion is that on the surface, Burger King doesn’t really gain much by moving to Canada.

While Canada’s statutory corporate federal tax rate is lower than the United States (15% versus 35%), both companies actually pay very similar effective tax rates (around 27%) when you include Canadian provincial taxes or deduct various loopholes available (the effective tax rate is the actual amount a company pays in tax, as opposed to the official statutory rate).

So despite what some people have said (*cough* Jason Kenney), that doesn’t quite seem to answer “why”:

Canada’s tax laws offer multinational corporations a plum deal that would make even Little Jack Horner jealous

What if the deal is more about an American corporation taking advantage of how Canada doesn’t tax the international profits of multinational corporations?

Here’s what Bloomberg’s Matt Levine points out:

“So the purpose of an inversion has never been, and never could be, and never will be, ‘ooh, Canada has a 15 percent tax rate, and the U.S. has a 35 percent tax rate, so we can save 20 points of taxes on all our income by moving.’ Instead the main purpose is always: ‘If we’re incorporated in the U.S., we’ll pay 35 percent taxes on our income in the U.S. and Canada and Mexico and Ireland and Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, but if we’re incorporated in Canada, we’ll pay 35 percent on our income in the U.S. but 15 percent in Canada and 30 percent in Mexico and 12.5 percent in Ireland and zero percent in Bermuda and zero percent in the Cayman Islands.’

Once you understand that, it’s obvious that the appeal of this strategy will vary in direct proportion to how much business you do in the U.S. and how much you do in, say, Bermuda.

Now, you might naively say: I doubt a lot of multinational companies do a lot of business in Bermuda! But I just told you that was naive. The key tricks are really to:

- put a lot of your income in Bermuda, and

- then never pay U.S. taxes on it.

…. If the parent company is a U.S. company, then eventually that Bermuda sub’s net income will be taxable in the U.S. anyway. But if the parent company is Canadian or Dutch or Swiss or whatever, then the Bermuda sub’s income will never be taxed.…. So if it moved to Canada, the roughly half of Burger King’s tax bill attributable to its U.S. restaurants wouldn’t change. Only the half of the bill attributable to its restaurants abroad would — and that only when it repatriates the money.4 Its restaurants in Canada would go from paying 15 percent to Canada now, and 20 percent to the IRS eventually, to paying 15 percent to Canada and zero percent to the IRS. Its restaurants in the Cayman Islands would stop paying taxes to anyone, because that is how it goes in the Cayman Islands.”

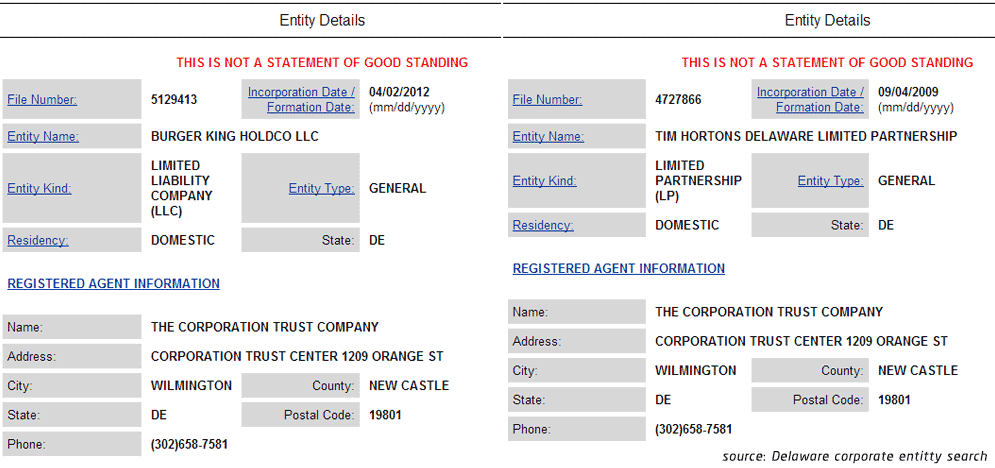

King and Horton: a dodgy history dating back to time as ex-roommates in Delaware

Photo: Calgary Reviews, Kermitmorningstar, used under CC BY 2.0.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate