Fraser Institute: capitalism may create less equality than tin-pot dictatorships

The Fraser Institute compares Lululemon, maker of "yoga-inspired clothing," with "authoritarian leaders and dictators."

Maybe tyranny isn’t so bad after all!

In the Fraser Institute’s latest adventure into the fun and exciting world of comparing apples to oranges, the right-wing think tank discovers that some countries with dictators and/or widespread corruption have less inequality than some countries operating under laissez-faire capitalism.

So, the Fraser Institute wonders: maybe inequality isn’t such a bad thing after all?

“When deciding how much any society should worry about inequality,” says Fraser Institute executive vice-president Jason Clemens, “citizens should first understand the way income and wealth are earned.”

And to explore this mystery in greater detail, the Fraser Institute compares Lululemon, maker of “yoga-inspired clothing,” with “authoritarian leaders and dictators,” such as former Indonesian strongman Suharto.

As the Fraser Institute’s executive summary elaborates:

“How income is earned or wealth amassed matters with respect to the degree to which citizens should be concerned about inequality … One example is Chip Wilson, founder of Lululemon, who has an estimated net worth of $2.2 billion. As an entrepreneur, Wilson took enormous risks to innovate and develop a line of products that consumers wanted and were willing to pay for … Another way to ‘earn’ income and amass wealth is through corruption … An example discussed in the essay is Indonesia’s Suharto family, which reigned for decades, embezzling between US$15 billion and $35 billion in a relatively poor country.”

Call it ethical inequality.

The Fraser Institute argues inequality that is the byproduct of wealth amassed by “special privileges and protection from governments” by dictators is different from inequality that is the byproduct of wealth generated by corporations, because “not all inequality is equal.”

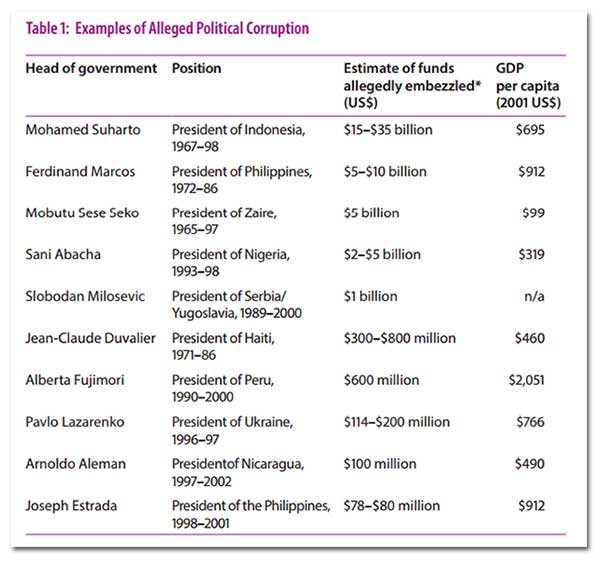

To underline this point, the Fraser Institute provides a helpful chart listing various tyrants and war criminals:

True, it’s hard to argue against the idea that a “yoga-inspired” clothing company is different from Slobodan Milosevic. Still, it feels like Fraser Institute might be missing the bigger picture here.

Plus, the Fraser Institute forgets that many profitable businesses rely governments making public investments in infrastructure that build and sustain their businesses.

Not to mention: where would companies find skilled workers if it wasn’t for public schools and post-secondary education? Or does the Fraser Institute consider that another example of the “special privileges” of government?

And what about when big business lobbies government to protect, oh, let’s say, the tobacco industry? What does the Fraser Institute think about that?

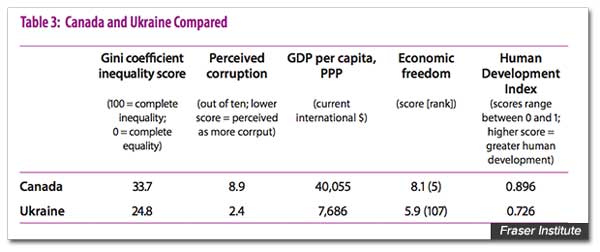

The Fraser Institute goes on to compare Canada with Ukraine, using data on inequality and corruption from several years ago under what was widely viewed as a pretty anti-democratic and kleptocratic regime.

They note that although Ukraine was largely perceived to be corrupt, Ukraine enjoyed less inequality than Canada:

“More equal societies, such as Ukraine, are not necessarily better off than countries with higher levels of inequality.”

On the other hand, the reason Ukraine appears to be so “equal” is that everyone is equally poor – the Fraser Institute forgets to mention how Ukrainian industry crumbled following the collapse of the Soviet Union, leading to widespread poverty and corruption and, for much more complex sets of reasons than they lay out, never recovered.

In fact, even the government at the time conceded their policies encouraging “cheap labour” had created a situation where even those with good jobs found themselves in poverty.

But according to what the Fraser Institute calls their “simplified approach,” it’s either a choice between inequality or corruption. So take your pick.

But hey, don’t worry: the “inequality” created by economic freedom “provide enormous benefits to society,” benefits like, you know, wearing clothing made in countries with low-wages, poor working conditions and less freedom.

Photo: bjornfree. Used under Creative Commons license.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate