Winnipeg Police Board Admits to ‘Series of Human Rights Violations’ During Coronavirus Pandemic

Winnipeg police chief points blame at Brian Pallister’s government

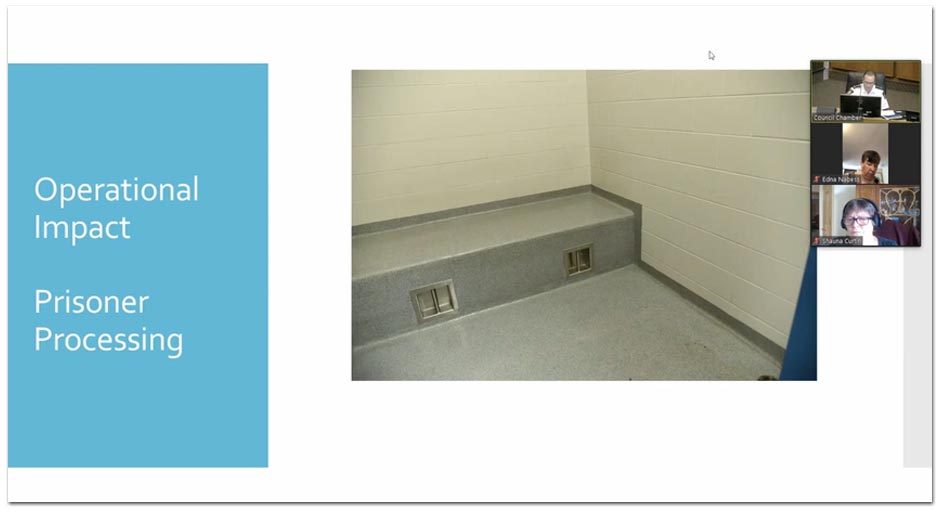

Winnipeg Police Chief Danny Smyth told the city’s police board on Monday that his officers held prisoners in small, windowless cement rooms with no toilets, mattresses or food service for up to 43 hours.

The police board agreed that what the chief described constituted a “human rights violation or a series of human rights violations.”

Smyth said that COVID-19 restrictions limiting police’s ability to hold people at the Winnipeg Remand Centre has forced prisoners to spend long hours at the Police Headquarters in conditions violating their human rights.

Winnipeg Police Services (YouTube)

The Remand Centre is a detention centre for those who are awaiting trial, court decisions on charges and transfer to a correctional facility.

The police chief disclosed that over the past two months, over 100 prisoners have been kept in small cells at police headquarters for extended periods. The lights were always on and officers were required to disrupt prisoners’ sleep to check for medical distress.

“We’ve had prisoners urinate in these rooms, defecate in these rooms and vomit in these rooms,” Smyth said, despite attempts to coordinate bathroom breaks.

“The risk of harm to one of these prisoners because of the way they’re being treated at this point has greatly increased.”

Secretary of the Winnipeg Police Board Shauna Curtin said Smyth described “a human rights violation or series of human rights violations in terms of what’s happened with inmate transfer and holding.”

Smyth said the Ministry of Justice did not “meaningfully respond” when he first raised the issue on May 5. He said the Remand Centre should allow new inmates, claiming the risk of COVID-19 spreading has lowered.

“The risk of contracting COVID has greatly diminished in our community, and the risk of harm to one of these prisoners because of the way they’re being treated at this point has greatly increased,” he said.

Smyth said those detained fell into two categories: people who were intoxicated and people who were violent.

Corey Shefman, an Aboriginal rights lawyer practicing in Manitoba and Ontario, thinks Smyth could have done more.

“The first time an individual was kept in the lockup cell for 24 hours, let alone 48 hours, that information should have been made public and there should have been an accountability mechanism through the Winnipeg Police Board or someone else to take steps to ensure that it didn’t keep happening,” Shefman told PressProgress.

He added that police shouldn’t throw intoxicated people in jail in the first place.

“Take them to a shelter or take them to another safe place,” Shefman said. “The City of Winnipeg has a whole bunch of vacant hotels at this point that aren’t being used by anyone.”

“Assuming people don’t have a home of their own to go to, figure out some other solution that doesn’t involve essentially warehousing people into a tightly confined, overcrowded environment they have no business being in.”

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate