Truckers Say They’re ‘Not Confident’ in New Training Guidelines Brought In After Fatal 2018 Humboldt Crash

New University of Saskatchewan study suggests long haul truck driver training does not meet driver needs in Canada

Long haul truck drivers are “not confident in the current training guidelines” for new drivers in Canada, says a new study from the University of Saskatchewan.

One-third of long haul truck drivers who participated in the study said they have previously been involved in a crash. In Canada, fatal collisions involving long haul truck drivers make up over 50% of fatal crashes in the commercial vehicle sector.

Following the 2018 Humboldt crash that killed 16 people after a collision between a semi-truck and a charter bus, the provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta introduced new Mandatory Entry Level Training safety programs for truckers.

Prior to Humboldt, the only province with a MELT program was Ontario.

Source: University of Saskatchewan report

“It’s a great first step, it’s a way to regulate training standards across Canada,” Alexander Crizzle, Director of the USask Driving Simulator Laboratory told PressProgress.

However, MELT programs vary by length and content across Canada. After two years running, there have been no published studies assessing whether any of the MELT programs have actually made highways safer.

“Are any of these programs effective in reducing crash risk? I don’t think we know that just yet,” Crizzle pointed out.

A national standard for provincial MELT programs was introduced last year. However, the USask study states that “the opinions of the drivers themselves have not been adequately considered” in the development of the guidelines.

Based on feedback from over 200 truck drivers, the study recommends a standardized federal MELT program that adequately consults truck drivers to ensure consistent training.

For example, Saskatchewan’s MELT program is currently designed for 121.5 hours, which amounts to three 40-hour weeks. Ontario’s MELT program is only 103.5 hours. Long haul truckers argued training should be double or triple in length, somewhere between eight to 12 weeks.

“They might argue that the skills are going to be identical, but the activities are going to be a little bit different and the amount of training is going to be a little bit different,” Crizzle said. “So I’d be very curious to see which MELT program actually produces the best results.”

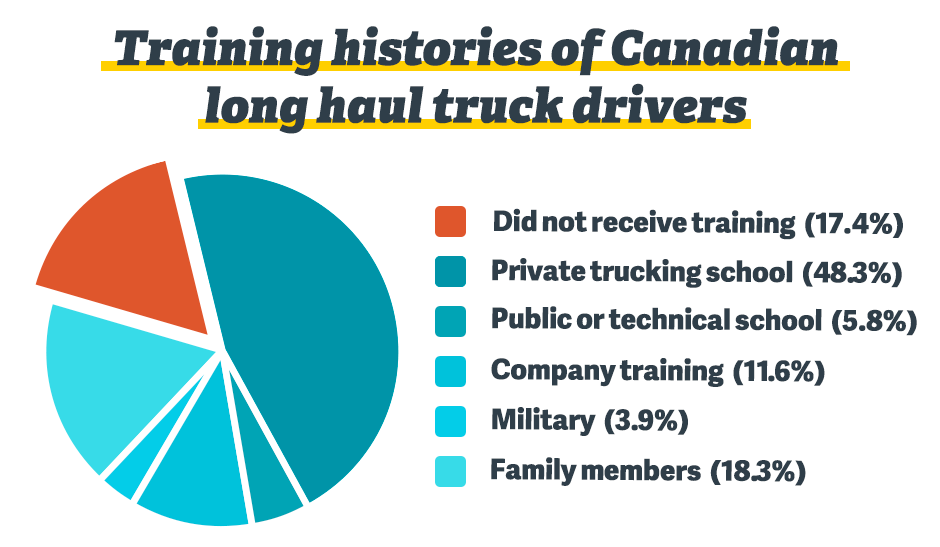

Drivers who obtained their license prior to 2019 were not required to take the new MELT programs. Most study participants received training from private driving schools (48%), while others said public or technical schools (5.8%), company training (11.6%), the military (3.9%) and family members (18.3%).

Another 17.4% reported having no training at all.

Source: University of Saskatchewan report

The study, which canvassed truckers at truck stops in Saskatchewan and Alberta, found most truckers felt public or accredited driving schools provided the best training, as opposed to private, non-regulated ones.

One driver explained: “The training programs that they have, the stuff that they teach the guys is just bare minimum to get them, give me money and get out of my school kind of thing, it’s just not enough, they need more.”

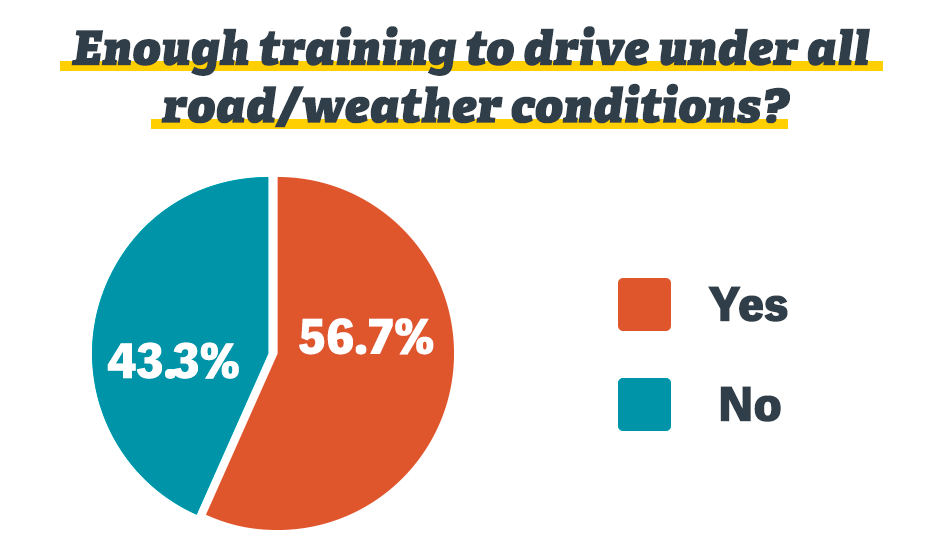

Many truckers said a key component that was missing from driver training was experience driving in different weather and terrains, as well as at night.

“Driving a truck around the city here is not the same as driving a truck over the Coquihalla highway in the middle of the winter,” one driver said.

Crizzle said working conditions need to be addressed to improve safety, noting that the sedentary, isolated lifestyle of truck driving can have negative long term health impacts on workers.

Paying truckers by the mile, rather than by the hour, can pressure them to drive as far as they can in one day, which increased stress and fatigue — a lack of truck stop infrastructure also means many drivers do not get adequate rest.

These conditions lead to high turnover in the industry and fewer drivers with expertise to train new hires.

One driver explained: “This company I worked for … they’d take new drivers and say well here you’ll get an extra two cents for training this guy, but the guy that’s doing the training, he drives for 12 hours, hops in bed and says here you go … They need actual trainers.”

“Companies don’t wanna pay experienced drivers what they otta be paid to truly put in the effort to wanna train rookie drivers,” said another.

The Saskatchewan Trucking Association recently lobbied the Saskatchewan government regarding the “approach to immigration for the trucking industry” to find a solution to the “truck driver supply issue.” The STA did not return PressProgress’ requests for comment.

Crizzle said truckers are also concerned about training for new immigrants.

“They were concerned that new immigrant drivers might pass in terms of getting their truck driver license, but they do so with support of an interpreter, and then when they actually drive on the road, they have a hard time understanding the signs.”

According to Saskatchewan Government Insurance, the province’s MELT curriculum is only offered in English. A Weyburn driving instructor explained to PressProgress that individual schools may use their own discretion to offer language supports, though the final exam must be completed in English.

An SGI representative also noted the “changes under MELT have not been fully implemented.” In March, the province will expand the MELT program requirements to include the agriculture sector and non-residents.

Crizzle would like to see more research on MELT programs to provide more concrete data on improving safety.

“It’s a very confusing sector to try to say, ‘Okay, this works and this doesn’t’ because there are stark differences everywhere.”

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate