More than half of Ontario’s postsecondary jobs show signs of precarity

Precarious work is a serious, and growing, problem at Ontario’s colleges and universities

A degree may have gotten more expensive, but don’t expect the added costs of tuition to trickle-down to your school’s frontline workers…

According to a new analysis from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, various forms of precarity are now the norm for a majority of Ontario’s 140,000-strong postsecondary workforce.

Using Labour Force Survey data from Statistics Canada, the study finds that “53% of post-secondary education workers in Ontario are, to some extent, precariously employed.”

The postsecondary workforce encompasses a diverse range of jobs, from professors and teaching assistants to managers and support staff, with stability and security unevenly distributed across different job categories.

For this reason, the report’s authors identify three major indicators of precarity:

“Indicators of precarity, including workers holding multiple jobs, more temporary work and unpaid overtime, are on the rise, though not uniformly, and not for everyone.”

Source: CCPA

So what does the growth of precarious work look like at Ontario’s postsecondary institutions?

Among the different jobs analyzed, the authors found an increase in work categories that are more precarious – such as research and teaching assistants – coinciding with a decline in traditionally more stable jobs, such as library work. There has also been an increase in precarious work within certain job categories, which translates to an increased proportion of temporary workers in student services and plant operations, administration and college academic staff. Finally, we have identified a steady decline in the proportion of full-time university instructors and college academic staff in the sector.”

As a result of these trends, some 53% of postsecondary jobs now show at least one indicator of precarity (temporary work, juggling multiple jobs, or work that goes unpaid).

What’s more, the trend toward these precarious working conditions has gone up since the late 1990s.

Perhaps most glaringly, “the proportion of workers with two indicators of precarity has increased from a low of 5% in 1998 and 1999 to a high of 15% in 2005, 2014 and 2015”, landing at 14% in 2016.

None of this, the authors point out, is happening in a vacuum:

“Across Canada, average weekly earnings from March 2016 to March 2017 only grew by 0.9%, i.e., less than inflation. Meanwhile, household debt continues to creep upward, sitting now at 172.1% of income, according to the most recent statistics. But that’s only the average: the ratio of debt-to-disposable-income for bottom-income-earning households was 333.4% and for the top it was 128.3%. In effect, we are witnessing a perfect storm: incomes for the majority of workers are not keeping pace with the cost of living, household debt is ballooning, and, as discussed in this report, there is a documented rise in precarious work.”

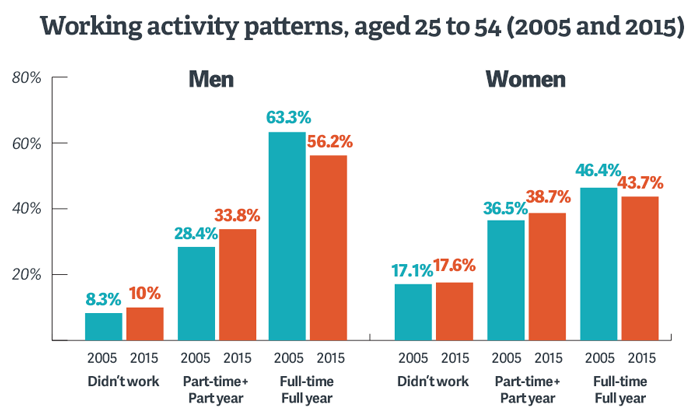

Indeed, Statscan data from November, 2017 found that the quality of Canadian jobs continues to fall while precarious work continues to rise across the economy as a whole.

Source: Statistics Canada

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate