Many Canadians nearing retirement don’t have the savings they need to avoid poverty

Poverty rates for Canadian seniors are on the rise.

So much for “Freedom 55.”

According to a new report authored by statistician Richard Shillington and published by the Broadbent Institute, poverty rates for Canadian seniors are on the rise.

And as older Canadians near retirement age, a lack of savings could mean the problem is about to get a lot worse.

Seniors poverty increasing

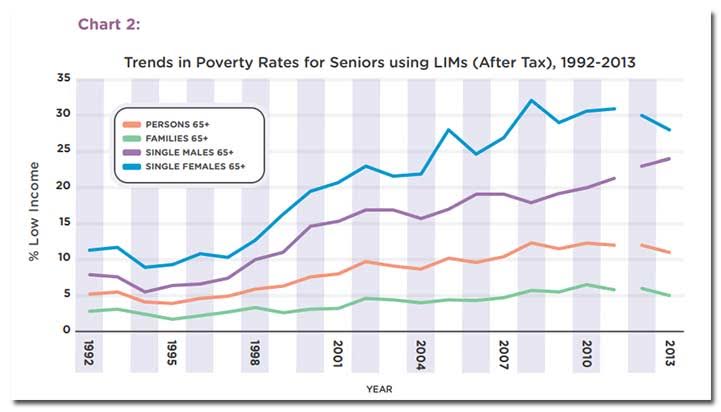

Poverty among Canadian seniors fell during the 1980s and 90s, hitting an historic low of 3.9% in 1995. Since the mid-90s, however, there has been a worrying trend in the other direction – hitting 11.1% (or one in nine) in 2013.

Among seniors, poverty rates vary substantially by gender and between those who are married or single. Single women are most likely to experience poverty, at a staggering rate of nearly 30%.

The savings crisis

Without bold government action, Shillington predicts that these trends are likely to worsen.

A major cause of poverty after retirement is the lack of an employer pension, particularly among those who earned average incomes throughout their working lives.

The report finds that half of Canadian couples between 55 and 64 have no employer pension between them. To make matters worse many of these couples have little to fall back on at retirement, with about half of families without an employer pension having virtually no savings.

Even taking into account the support retirees will receive through government programs such as the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), many will likely see a significant fall in their living standards post-retirement.

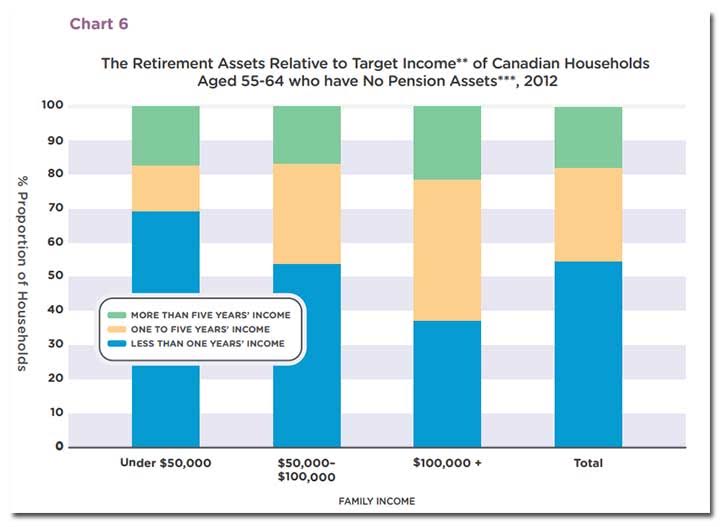

Calculating the needs of different income groups after retirement (the “target income”) the report finds that many, even those going into retirement on the back of higher incomes, have not been able to save adequately.

Over half (55%) have assets that represent less than one year’s worth of the savings they need to supplement the support they will receive from government programs. Among the lowest income group, the figure is nearly 70%.

Shillington concludes that the looming crisis needs to be taken more seriously:

“Poverty rates for seniors have been trending up since 1995. Rates remain unacceptably high for single seniors—especially women—and the worsening trends in pension coverage point to further increases in poverty in the future…A substantial proportion of middle-income Canadians without an employer pension plan will face a dramatic drop in living standards during their retirement years. [There is] an urgent need to address this situation…The panoply of public policies offering “voluntary” options for saving—such as RRSPs, TFSAs, group RPPs, and the more recent Pooled Registered Pension Plans—have demonstrated their inadequacy to address the shortcomings in declining workplace pensions and a Canada Pension Plan with limited benefits. These results suggest an important role for incentives to expand workplace pensions (particularly of the defined-benefit variety), and to enhance benefits of the Canada Pension Plan.”

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate