Why Is The Pandemic’s Economic Harm Disproportionately Impacting Young Women?

Many have called it a “she-cession,” but some women are taking a bigger hit than others

There’s no doubt the pandemic has caused global economic harm — from record high unemployment, to waves of restrictions causing businesses to temporarily shut down, to a massive decrease in tourism, we’re living through an economic crisis comparable to the great depression. But like the spread of COVID, the pandemic’s economic devastation is disproportionately impacting certain groups.

Women, especially young racialized women, are over-represented in layoffs, leading many to become unemployed long-term, or drop out of the workforce altogether. Past recessions show that youth unemployment tends to remain high years into economic recovery, and those years out of the workforce can have long-term effects on young workers’ employment prospects and earnings.

“Women were much more significantly impacted by the layoffs and loss of hours due to the closure of non-essential businesses.” @DavidMacCdn looks at who is falling through the cracks of Canada’s EI/CERB system by gender. https://t.co/eeslRWFxBd#COVID19Canada #canfem

— The CCPA (@ccpa) April 27, 2020

But why has the pandemic economy been so terrible for young women?

Over half of women workers are employed in one of the five Cs: caring, clerical, catering, cashiering and cleaning. When provinces like Ontario implemented stay-at-home orders, restaurants and retail shops ceased or dramatically reduced business, and their employees were the first to feel the crunch.

While industries that can easily transition to remote work, like real estate, insurance and finance, have actually made gains in employment over the past year, lower wage industries have seen employment rise and fall with the tightening and easing of lockdown orders.

The impact of 2020’s lockdowns on women’s employment is reflected in CERB: more women accessed the program than men, and declines in total hours worked were larger for women than men in every age and income bracket.

#StarExclusive: The statistics are clear: across the country, women and low-wage, racialized workers in precarious employment were hit hardest by this year’s COVID-19 job losses.

Here are the findings from a survey of CERB recipients: https://t.co/EKa6jSt1uU

— Toronto Star (@TorontoStar) August 14, 2020

Even when businesses in those sectors are able to operate at reduced capacity, layoffs aren’t evenly distributed.

Angella MacEwen, a senior economist with CUPE, says women are more likely to be in client-facing positions, or work in establishments that aren’t considered essential.

“In retail, there’s been a bigger impact for young women within that industry, and so then I think you have to break it down a little bit more,” she told PressProgress. “What types of retail do women tend to work in?”

MacEwen said women are more likely to be employed in malls and stores that fall outside the definition of “essential” retail. For example, an argument can easily be made to keep a hardware store open in a partial lockdown; arguing for clothing stores to be kept open is more difficult.

Likewise, within a restaurant, women are more likely to be servers or hosts as opposed to cooks. When a restaurant only offers take-out and delivery, it doesn’t need a full roster of servers, some of whom will be laid off.

Young women, especially those who are working while in school, are overrepresented in these sectors — in the summer of 2019, nearly two thirds of employed students worked in food services, accommodation, retail or recreation and culture.

Unemployment rates for racialized groups have been consistently higher throughout the pandemic, adding yet another barrier for young racialized women.

ICYMI: Canada’s unemployment rate in July was higher for all primary groups of racialized Canadians compared to white Canadians, according to Statistics Canada’s labour force survey for that month, the first to feature disaggregated race-based data. https://t.co/oeY3w36kJZ

— iPolitics (@ipoliticsca) August 8, 2020

Young workers are also less likely to have the benefit of years of experience, and therefore contacts in their industry and good reputations. When industries that rely heavily on connections, like arts and culture, slowly begin to recover, young workers and those just starting their careers aren’t first in line for job opportunities.

Alix Reynolds relocated to Edmonton, Alberta to work as a theatre director not long before the pandemic began. While she’s seen more experienced theatre workers find enough work to get by throughout the pandemic, with only one show under her belt in Edmonton, she’s found it difficult to find work.

“Because I didn’t have any contracts already when the pandemic started, now it’s going to be an extra year before I could potentially get contracts because people want to still put on all the shows that they never got a chance to put on,” Reynolds told PressProgress.

Gendered expectations strike again when women are laid off or are able to work from home.

The patriarchal expectation that women are suited to caring for others means that when women have been laid off or had their working hours dramatically reduced, many will take on care work at home. With schools closed and fears around the safety of long-term care homes, demands for women to care for children and aging relatives at home have skyrocketed.

These expectations are far from fair, but they’re nothing new. Even in pre-pandemic times, women typically took on the “second shift”: hours more unpaid child care and housework than their male counterparts.

Statistics vary from country to country, but in Canada the most recent data revealed women spend over six hours more than men on housework every week. When it comes to elder care, women are more likely than men to be caregivers.

Statistics Canada

Though EI offers “compassionate leave” for workers who have had to take time off work to care for their relatives, it only covers 55% of the applicant’s earnings.

Even when women are able to work from home, they often take on the majority of care work. As many mothers can attest, working a full-time job from home while taking care of children didn’t make the division of labour more equal — in fact, it had the opposite effect. During the pandemic, the “second shift” suddenly became even longer.

Given these circumstances, it’s not surprising that some job seekers would become discouraged and join what statisticians call the “long-term unemployed,” which refers to workers who are not employed and not actively looking for work.

After losing her job as a teacher following Brian Pallister’s cuts to education funding in Manitoba, Hayley Sharkey started working in a movie theatre at the end of 2019. She hoped that the less demanding workload would give her time to reevaluate what kind of career she wanted to pursue.

Then the pandemic hit and the theatre abruptly closed. The consequences of two sudden job losses, a global health emergency and filling out hundreds of job applications with few call-backs took its toll on Sharkey’s mental health.

“When I found myself in this situation I was kind of lost and already really mentally exhausted, and it was just too much all at once,” she told PressProgress.

Though she was initially hesitant to return to education due to fears of contracting COVID, Sharkey eventually began applying for jobs in education. She was disappointed to find an overworked, stressed workforce that was struggling to meet the challenges of the pandemic.

Economists like MacEwen think that women’s connections to the care economy – which typically includes elder, child and health care – could end up helping women’s employment recover post-pandemic.

“It really does seem to be that on the one hand, the pandemic has affected a lot of jobs that are predominantly female, but then on the other hand, there are going to be hirings for positions that are still predominantly female, like early childhood education and personal support workers,” said MacEwen.

The federal government has pledged to invest billions in child care, which they say would make it both more accessible, and ideally, much less expensive. This would give women with young children the option to remain in the workforce instead of stalling their careers due to lack of child care options.

Since child care workers are over 95 per cent women, investments in this sector have the potential to expand opportunities, increase wages and improve working conditions for women workers.

Much the same can be said for elder care – when comprehensive, affordable services are available, care work is less likely to fall on unpaid family and friends to pick up the slack.

However, as it currently stands, these sectors have few well-paid jobs. The pandemic revealed a staffing crisis in long-term care, particularly at for-profit facilities, which rely on low-paid workers. Before some provinces introduced single-site orders, many had to work at multiple facilities to make ends meet.

Labour group calls for premium wage increase for personal support workers https://t.co/YjzGcL6kOQ pic.twitter.com/81jaCCKcAt

— CBC KW (@CBCKW891) April 23, 2020

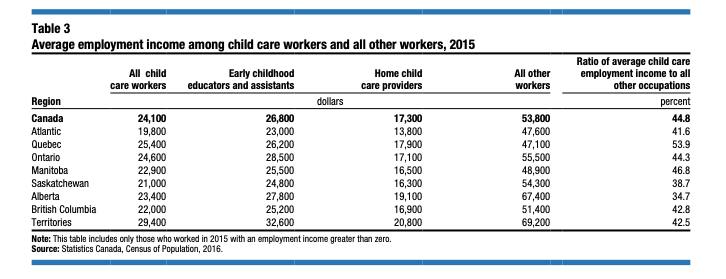

Child care suffers from similar issues. On average, early childcare workers make $24,100 a year — less than half the average annual salary in Canada, and they rarely have job benefits. As a result, many leave the field after only five years.

Statistics Canada

Armine Yalnizyan, an economist and Atkinson Foundation fellow, says this high turnover affects workers who stay in the industry.

“When you have high turnover it is very difficult to do two things: provide good quality care, number one. And number two, organize workers so that they can get better wages and working conditions,” she told PressProgress.

In order for those investments in the care economy to truly improve women’s employment, Yalnizyan said, Canadians need to elect governments that are serious about providing care that addresses the needs of both women who need those services, as well as the workers who provide them.

For Yalnizyan, the care economy has the potential for immense change.

“If we understood the care economy to be the foundation of everything else, which was what the pandemic kind of revealed, and we make every job in that sector a good job, we would have the foundation for the next middle class early 21st century, much in the same way that manufacturing provided the backbone of the middle class from the 1960s to the 1970s,” she explained.

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate