Renting a 1-Bedroom Apartment in British Columbia Now Costs Nearly Double BC’s Minimum Wage

BC’s rental prices are the highest in Canada – and the problem is not just in Vancouver too

It is nearly impossible to find affordable rental housing in British Columbia and the cost of renting a one-bedroom apartment is nearly double the province’s minimum wage, according to a new report.

A new study from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives sheds light on rental wages across Canada and highlights the challenges minimum wage workers are facing with housing affordability across the country.

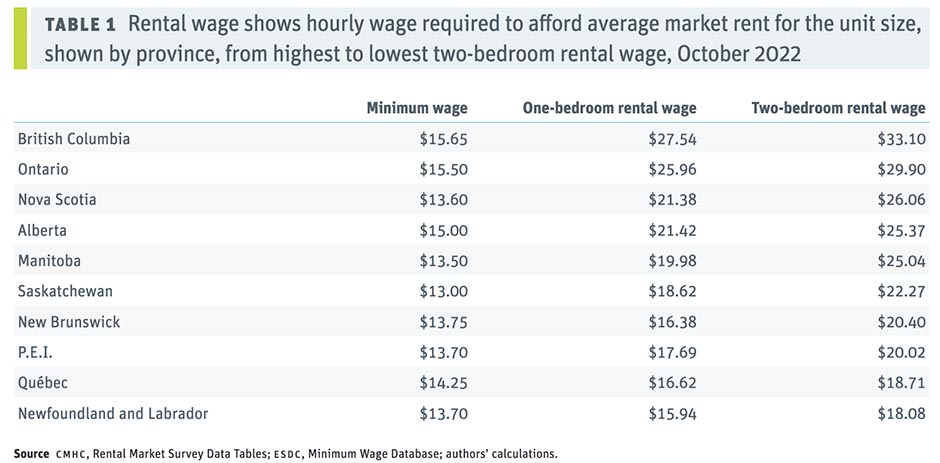

The report compares minimum wage workers’ wages with the cost of rental housing and concludes that in every province in Canada, the rental wage for a one or two bedroom apartment is higher than the minimum wage.

In BC, things are particularly bleak.

“BC is extraordinarily expensive,” report co-author David Macdonald, senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives told PressProgress. “In Vancouver, you need to work over two full-time minimum wage jobs to afford a one bedroom apartment.”

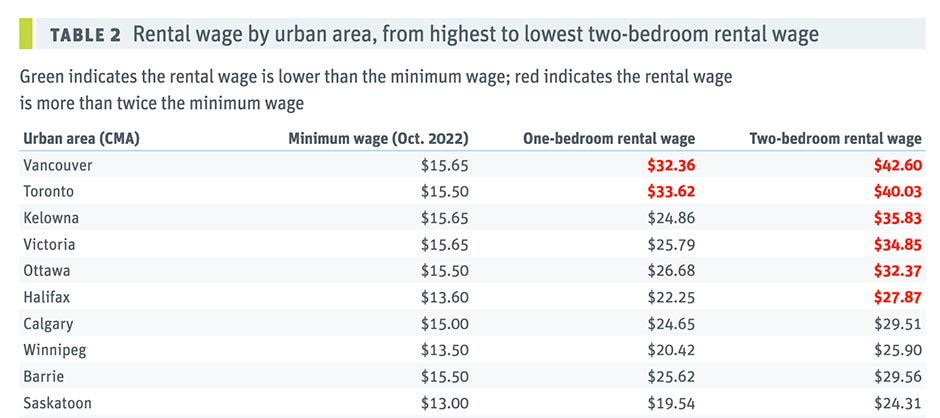

According to the CCPA’s report, while BC minimum wage workers earn $15.65 per hour, it would require an hourly wage of $32.36 just to afford a one-bedroom apartment and $42.60 to afford a two-bedroom apartment.

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

But Vancouver isn’t the only BC city getting recognition for the wrong reasons.

In Kelowna, a one-bedroom apartment would require an hourly wage of $24.86 while a two-bedroom would require a wage of $35.83 per hour. Similarly, one-bedroom apartments in Victoria would require a job paying $25.79 per hour and two-bedrooms require $34.85 per hour.

“Kelowna and Victoria are the third and fourth most expensive cities for a two bedroom apartment,” Macdonald said.

“Kelowna has the dubious distinction of seeing the biggest increase in minimum wage hours that would be required to afford a two bedroom apartment of any of the 37 big cities in Canada over the last four years.”

Overall, British Columbia’s average rental wage for a one-bedroom apartment is $27.54 while a two-bedroom apartment is $33.10 – the highest average rental cost of any province in Canada.

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

“Across the country, there’s only 10 Out of the 37 cities that we looked at that have even a single neighborhood where you can afford a one bedroom apartment at minimum wage,” Macdonald said, adding that the issue can’t just be chalked up to supply when it comes to rental affordability.

Supply is one of the potential solutions—but isn’t a sufficient answer alone, Macdonald added.

“Supply matters, but the type matters as much as the more supply matters. If you’re going to build mansions in farm fields around big cities, that’s not going to do anything for rental affordability. What’s required is purpose built rental,” Macdonald said.

“What’s required is that purpose built rental be non market rents. So these are affordable rents that aren’t whatever the market will bear – they’re affordable amounts that people could afford.”

Macdonald says that the current housing strategy also relies too heavily on the private sector.

“The federal government really used to be the driver of the construction of affordable housing, certainly, in the 70s and 80s. And that really dried up at the end of the 1980s. And we haven’t seen that kind of construction in 30 years,” he added.

“It’s still very much premised on the private sector delivering on the national housing strategy.”

Wage suppression is also contributing to the issue, with wages not increasing despite a “tight labour market.”

“We also need rent controls that are adequate, and where there are consequences if you attempt to evade those rent controls, to really tighten down on the exemptions that landlords can get to increase rents above the rate of inflation,” Macdonald said.

When it comes to the rebuttal that those who can’t afford rent “simply move out,” Macdonald says the situation isn’t as simple as that.

“People can’t live in big cities. And that’s particularly true in places like Vancouver,” Macdonald said.

“Businesses need workers, but workers can’t live there. And that becomes an issue for economic growth and for the vitality of a city. Having people live in your cities and afford to live there and have accommodation is part of the public good.”

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate