BC Passed an Anti-Drug Law. Community Groups Say It Will Target Unhoused and Racialized People.

Groups warn BC’s Bill 34 will have unintended consequences and disproportionately impact vulnerable communities

A coalition of drug users in Surrey, BC say a bill against outdoor drug-use will disproportionately impact unhoused people and target Indigenous and racialized communities.

The Surrey-Newton Union of Drug Users has penned an open letter calling on the BC government to withdraw Bill 34, which they say will give “police more power to profile and approach unhoused people.”

Bill 34 bans public drug use, meaning in communities without accessible safe consumption or overdose prevention sites, there is nowhere to safely use drugs without the risk of being arrested. The bill contradicts BC’s decriminalization pilot, which was intended to minimize interactions between people who use drugs and police.

SNUDU members say that given Surrey’s diverse population, racialized communities will also be profiled and the lack of existing resources means people simply have nowhere else to go.

On Monday, the Harm Reduction Nurses Association also issued a statement, “asking the BC Supreme Court to declare Bill 34 unconstitutional, as it violates core rights and freedoms under the Charter.”

The HRNA says “Bill 34 will drive drug use further into the shadows and put the lives of our clients and community at risk.”

According to Fraser Health, Surrey has two safe injection sites, one with two spots and one with eight spots, and one safe inhalation site with a maximum capacity of 20 people.

Earlier this year BC’s coroner revealed that nearly two-thirds of overdose deaths came from smoking drugs, “yet only 40% of supervised consumption sites in the province offer a safe place for people to smoke.”

Amy Lynn Brown, member of SNUDU Womens Committee says that with resources having limited space and being concentrated in a specific area, they aren’t always accessible.

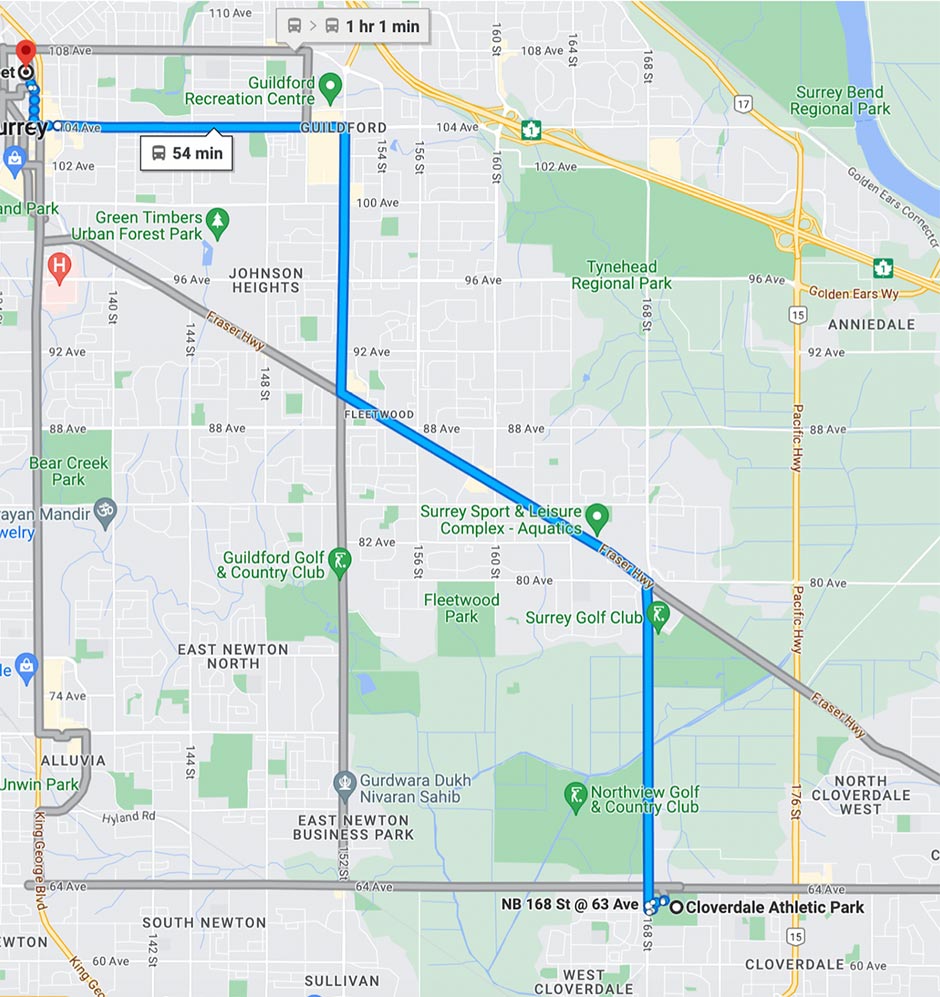

Brown says she has previously stayed at shelters in Cloverdale, while the only safe inhalation site in Surrey is located in Whalley—more than a one hour commute on transit.

The distance between central Cloverdale and the singular safe inhalation site in Surrey via transit (Google Maps)

“There needs to be more places for people to smoke their drugs and be safe and not have to worry about if anyone’s going to hurt them or if they are going to be killed or beat up or assaulted,” Brown told PressProgress.

“They need to have a place, even a tent or something out there for them to sit there and be safe and be warm.”

Brown adds that the toxic nature of the drug supply means that people may have unpredictable reactions to unregulated drugs.

“It’s getting worse and more people are going to die,” Brown said.

“We need a safe supply of drugs so people don’t have to rely on unregulated toxic drugs. And we need more safe places to smoke indoors, we really do.”

SNUDU Steering Committee member Elder Mona Woodward, also known as ‘Sparkling Fast Rising River Woman’, says the bill will further marginalize Indigenous women because Surrey has the highest urban Indigenous population in BC.

“We’re disproportionately overrepresented in the area of homelessness. And the homeless population is really high here in Surrey and we already feel the stigma of that to begin with,” Woodward told PressProgress.

“This is only going to intensify with this bill being passed and I’m just concerned about women going into isolation and that can expose them to more harm.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, UBCIC President says BC’s new drug policy “targets the most vulnerable Indigenous members of our communities.”

“Current drug use policy and practice disproportionately and negatively impacts First Nations users due to the complex and intersecting effects of colonialism and highly visible public drug use is generally a symptom of the spiraling crises of housing, affordability, and fatal overdoses,” Grand Chief Stewart Philip said in a statement to PressProgress.

“Without a full spectrum of culturally safe, voluntary, evidence-based services, this racist legislation will increase fatal overdoses and expose Indigenous people to further societal exclusion and police violence.”

Grand Chief Phillip also adds that Indigenous people are disproportionately represented in the number of fatal overdoses in BC.

“Across BC, Indigenous people fatally overdose at 5.9 times the rate of other BC residents, but seven and a half years after the crisis was declared a public health emergency, essential services, like overdose prevention sites, are unavailable and inaccessible outside of a few urban centers,” Grand Chief Phillip said.

“This legislation is not a solution; on the contrary it stands to further isolate and abandon community members who are struggling, and is a direct attack on unhoused and First Nations people that will cause countless more deaths.”

Woodward said she herself has struggled navigating resources in Surrey and as an Indigenous woman who has been unhoused, she feels that her own vulnerabilities and past experiences are being disregarded as people are pushed into the shadows once again.

“I’m a survivor of sexual assault. I don’t want to be a throwaway. I’ve woken up naked from the waist down and the guy thought I was dead,” Woodward said. “This is only going to put me in isolation.”

Woodward adds that in case of an overdose, using drugs alone or in discrete locations means no one is around to help.

“The biggest gap in the resources is a safe place to go to do their drugs and to feel supported, and if there is an overdose, to know they’ll be quickly attended to.”

“I’m handicapped and I use a walker, and it’s really hard for me to get around anywhere to begin with, so traveling and further to be isolated is really scary.”

A lack of spaces for overdose prevention, and other accessible supports also mean a greater reliance on the already under-resourced Surrey Memorial Hospital, the only hospital serving Surrey’s large and geographically dispersed population.

Woodward and Brown say their experiences at Surrey Memorial have been stigmatizing and “dehumanizing,” but the toxic drug supply means more people will be admitted to hospital.

“With the toxic drugs it’ll be more people overdosing and more people going to the hospital,” Woodward said.

“This legislation is going to dehumanize Indigenous women even more, and I’m scared, I’m scared, I’m scared of the repercussions.”

160 people have already died from toxic drug overdose in 2023 in Surrey.

UPDATE: Following the publication of this story, Mike Farnworth, The Minister of Public Safety and Solicitor General responded to SNUDU’s open letter regarding Bill 34.

“We recognize that vulnerable and/or unhoused people often do not have many reasonable options for places to consume drugs, particularly in places that do not yet have adequate overdose prevention services, and our government is exploring how the regulations may address the impact of the legislation on this population.”

Our journalism is powered by readers like you.

We’re an award-winning non-profit news organization that covers topics like social and economic inequality, big business and labour, and right-wing extremism.

Help us build so we can bring to light stories that don’t get the attention they deserve from Canada’s big corporate media outlets.

Donate